Kolbe Times: How did your early experiences shape who you are today?

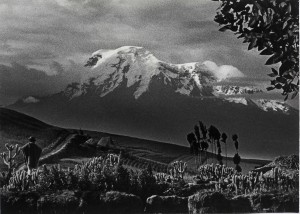

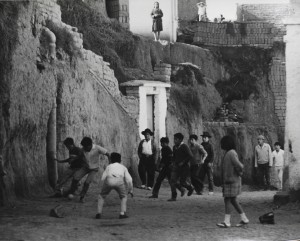

Ken: The most powerful influence on my life has been my parents. They were beautiful people who lived their entire life for others. They grew up in Mennonite communities in western Canada, left as newlyweds and spent over thirty years in South America working with indigenous people. They were with the first group of original Wycliffe Bible Translators who went to Peru in 1946. I was born two years later in a hotel in the foothills of the Andes. In hindsight, it seems to me that a hotel is a good place to be born – after all, a hospital is for sick people while a hotel is for travellers, and my whole life has been spent travelling and moving. Most of my childhood was spent in Peru and Ecuador, running barefoot in the Amazon, hiking in the Andes, riding buses through the big South American cities, and living in the midst of many different cultures. As a very blonde boy in the middle of Latinos and indigenous people, I was often a curiosity. And so it was in that setting that I apprenticed in photography, learning it from scratch. We built a photo lab, mixed our photo chemicals, and loaded our own bulk black and white film. I often think it was quite similar to 1960s technology for NASA, where pencil and paper and calculators took men to the moon.

After high school, a major spiritual crisis shook up my interior world and so I left Ecuador, moving to Miami and later Montreal, with my Leica camera stowed away in my bag. Life in North America was so different from what I had known. I found myself amidst the lost generation of the 60s and 70s, and we talked into the night about the aimlessness of life. This new world seemed driven almost entirely by material ends, especially when compared with the world I had grown up in, which was built around purpose, simplicity and community.

Beginning in 1978, I had opportunities to return to Latin America. The personal question for me was: “I was blessed with artistic gifts, developed now over many years. How can I reconcile the artistic calling with the needs of the poor, of social justice?”

Kolbe Times: You’ve spoken about the “concerned photographer” tradition. Can you tell us more about it, and why it seems to resonate with you?

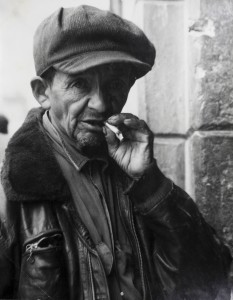

Ken: The tradition of “the concerned photographer” goes back to the early 1900s, with the documentation of social issues such as urban housing in New York City. It continued during WWII and the plight of the Jewish people, and then throughout the wars of Southeast Asia, as photojournalists immersed themselves in the horrors of violence and poverty in the slums. To follow in this tradition seemed a very natural outgrowth of my own journey, and my exposure to many cultures. But questions remained. Could photography bring hope and foster change? Or is it simply another self-centred tool on a journey of personal discovery? These questions pointedly reminded me of the necessity to draw closer to the heart of God, the merciful One who is on the side of the poor.

Many photojournalists who themselves are on the edges – or even beyond the edges – of the Christian tradition have seen this. W. Eugene Smith, Gordon Parks and Sebastiao Salgado are only a few of the photojournalists who have sought to right wrongs. But I would add that it’s important for any photojournalist who wishes to label himself as “a concerned photographer” to also seek beauty, goodness and human dignity. As well, it’s important to act with compassion and gentleness, being wise to the whole situation around the theme, and to respect and honour the viewers as well.

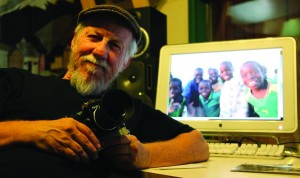

Kolbe Times: Tell us about the vision of Northern Rain Studio, and some of your projects.

Ken: Northern Rain is our small studio on our acreage. We rebuilt it from an old barn, and in this spot we’ve produced CDs, radio-dramas, short films, and held workshops.

But, to my mind, a studio is not really about a facility or its high tech gear. A studio is more about bringing people together and creating a setting where they can exchange their gifts. Over the years, we’ve been privileged to work on documentaries and promo pieces with a variety of clients across Canada on a wide range of subjects. I find that my background in still images and multi-image design has been a big help as I have moved into the film world. We are just finishing a short film entitled “Anna’s Goodbye,” and the project illustrated my passion – to work within small communities, inspiring people to appreciate their own stories and develop their skills.

We have a number of film projects on the drawing board which we hope will involve collaboration with communities in Latin America. The goal is really the same: to invest in people from a community, and make sustainable projects which give something back. It’s a big challenge, but I think it’s a good one.

More of Ken’s photos (click on images to enlarge):

Thanks again Ken. I’ll be getting in touch with you soon.. Ken Gosney

Pingback: Across the Decades, Dave Landers Ivested in the Lives of Students | Calloftheandes Weblog