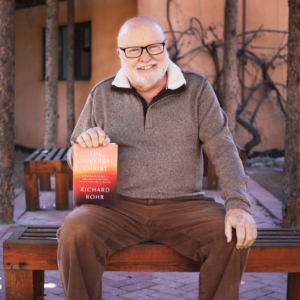

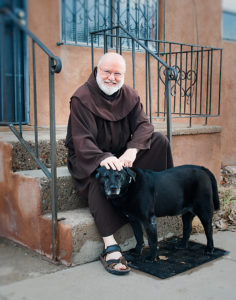

Richard Rohr OFM is a Franciscan priest, best-selling author of over 30 books, and founder of the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He is also one of the most influential and outspoken spiritual teachers of our time, whose work is grounded in Christian mysticism and the Franciscan tradition.

Richard Rohr OFM is a Franciscan priest, best-selling author of over 30 books, and founder of the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He is also one of the most influential and outspoken spiritual teachers of our time, whose work is grounded in Christian mysticism and the Franciscan tradition.

It was a great joy to talk with Fr. Richard about his life, his work and his new book The Universal Christ: How a Forgotten Reality Can Change Everything We See, Hope For, and Believe.

Here are a few video highlights of our interview:

Interview by Bill Locke

Kolbe Times: We’re so happy to talk with you today, and we really enjoyed your latest book, The Universal Christ. One of the big messages for us from your book is about an “incarnational worldview”; which is (to quote you in Chapter One) “the recognition of the presence of the divine in literally every thing and every one.” You also use the phrase “a Christ-soaked world”, which we love. If all creation is united in Christ’s presence, it has huge implications for how we should be living…and secondly, it’s great news!

Richard Rohr: It sure is – my goodness. And that we haven’t been able to make that clear up to now is so sad because to me, as I hope I say in the book, it’s obvious! You know, just this morning I found a quote in 2 Timothy, of all places, which I didn’t quote in the book – but let me quote it to you now. “Grace has already been granted in Christ Jesus, before the beginning of time. But it has been revealed only by the appearing of our Saviour, Christ Jesus.” That’s 2 Timothy 1: 10.

That verse is a summary of the whole book, and I only came across it after I finished writing it! It says that grace was from the beginning, but the ‘appearing’ happened in time. People who think this is not orthodox, or not Christian, or not Scriptural – well, we all really have a lot of learning to do, I think.

Kolbe Times: Another image from your book that jumped out for me is when you write “I love the image of fire, not for its seeming destructiveness, but as a natural symbol of transformation – literally, the changing of forms.” I think we misunderstand and overlook the powerful images of fire in the Old and New Testament, and how they suggest that God has a burning love for us.

Kolbe Times: Another image from your book that jumped out for me is when you write “I love the image of fire, not for its seeming destructiveness, but as a natural symbol of transformation – literally, the changing of forms.” I think we misunderstand and overlook the powerful images of fire in the Old and New Testament, and how they suggest that God has a burning love for us.

Richard Rohr: Well, you know, no one’s brought that up yet, and I’m really happy you were struck by it. We do tend to think of fire as destructive in spiritual theology and in alchemy – take the recent fire in Notre Dame in Paris. And, of course, it can be very destructive, but, you know, I would say fire is primarily transformative.

I think people who are more associated with the land see it that way, too. Farmers, forestry workers and native people know that fire can be a renewing force, even as it also can be destructive. And Jesus quite clearly believed in change. At the start of one chapter in the book, I quote a verse from Luke 12 where Jesus says, “I have come to cast fire upon the earth…and how I wish it were already blazing!” There is a universal pattern of growth and healing and change, through loss and renewal.

Kolbe Times: I really like how you start the book by sharing a story from the author Caryll Houselander. She describes quite a startling and life-changing experience that she had on a very ordinary train journey, when she suddenly saw Christ in all her fellow travellers. It reminded me of Thomas Merton’s vision in Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut Street. It also brought back memories for me of how I was affected by an experience I had many years ago, when I was out camping. I looked up into the stars and saw this magnificent cosmos, and I felt not just this immense space, but also this immense connection to everything. It changed me from that day onwards. Have you ever had a personal, life-changing epiphany like that?

Richard Rohr: Yes, and it rather parallels your experience. It was when I was growing up in Kansas, and my cousins all lived on big wheat farms. We would go out and spend the summer with them, and one time, behind some bushes in a rather hidden place, I found this very velvety grass. And I used to go out there secretly, and lie on it. I’d lay there on my back and look at the sky. And, you know, next time I go home to Kansas, I plan on tracking down that very spot again because I had the same experience as you – a feeling that I am totally connected here; I am totally safe here; I am totally good here. It came through looking at the immensity of the heavens, and the beauty of the stars. And this isn’t an uncommon experience! St. Francis felt the same thing. In one of his early biographies, it describes how he was such a party-goer in his youth, and one time he leaves a party and goes out in the yard – and then comes back and tells people much the same thing that you and I have been describing!

Richard Rohr dedicated The Universal Christ to his “beloved fifteen-year-old black Lab, Venus”, who died during the writing of the book.

Kolbe Times: I’d like to talk a little about the relevance of your book right now. I think many of us who are discouraged with all the negativity we hear. There’s seems to be a lot of polarization floating around in the world today, especially in the mass media – so there is a great relevance to your message. Can you comment on that?

Richard Rohr: I’m glad you see the book that way, Bill. This circling of the wagons, and identity politics, and identity low-level religion, is indeed very discouraging right now. It seems to be happening all over the world, too – not just in North America. So I thought about that as I wrote, and I also thought about the great need for us to re-establish Christianity as something based in creation itself. I say that in the book in several places. We can’t remain dependent upon a unique revelation that only happened 2,000 years ago, which, as you know, is just a blip in geological time. I’m not trying to downplay Jesus. But as that Second Timothy quote says, which I mentioned earlier, the grace was given from the very beginning! I often think, wouldn’t it be wonderful and appropriate if we would find that our religion is grounded in the very Earth we’ve been standing on since the beginning, all of us – this Earth that we all share in common. We’re all eating off of it, and we’re all living off of it. You know, it’s no surprise, we call it Mother Earth.

Now, I know to a lot of Christians, this will sound New Age-y and pantheistic, but that’s just not true. That’s too easy an ‘out’ – to just give it a name like that, and write it off, when it’s so grounded in the early Fathers of the Church, particularly those in the Eastern Church. And we in the Western Church have to be deeply aware of that. After 1054, we really didn’t study the Eastern Fathers very much. Now, in later history, to be honest, the Eastern Church didn’t study them much either. And so Orthodoxy became just as provincial, and just as ethnic, as we in the Western Church became. But what I’m talking about is the Big Tradition: Scripture…and let’s say especially the first six centuries, when Christians thought of the incarnation as a cosmic event, not just a personal event in the body of Jesus. But because most of us weren’t trained to read the Scriptures that way, I know it’s a jolt. But it’s a jolt that, right now, I think we have to endure, or we’ll become a tribal religion again.

A tribal religion will never save the world. It can’t! And, if I can say this to a Jewish person such as yourself, that was the original argument with Judaism. We knew it was our foundation, our ground, our matrix of spirituality, but Judaism was too tribal. It was too tied to ethnicity. And Paul in particular – who was a Jew himself of course, as were all the early followers – Paul says, no, the message is not tribal.

Kolbe Times: I remember going to St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome for the first time. We, as a family, were travelling around Italy and when we were in Rome, even though my wife and I weren’t Catholics at that time, we were drawn to St. Peter’s. We attended Mass, and we couldn’t help but feel that there was something unique about the synergy with all these different peoples from all around the world taking part.

Richard Rohr: I’ve heard that many times.

Kolbe Times: It seemed to us there was nothing else quite like it – the power of universality, the coming together, the trusting of one another, the generosity of spirit.

Richard Rohr: Yes. I remember feeling the same thing on my first trip there, when we still spoke Latin during Mass, and that whole thunderous crowd would begin the creed: “Credo in Unum Deo”; “I Believe in One God”. You could tell there were people from all over Europe, Asia, South America, North America, Africa – it was a marvellous experience. I don’t care much for the triumphalism of St. Peter’s, but if you can overlook that, there’s still a universality there that’s quite wonderful. I hope I make the point in the book that the word Catholic means ‘universal’. If only we would have capitalized on that! But we became more Roman than Catholic, and that’s really an oxymoron. Roman is the adjective that got applied after 313 A.D. In the first centuries, we were just calling ourselves the Catholic or ‘universal’ church, which is why that phrase is still used in the creed…and spoken by Methodists and Lutherans and Anglicans.

Kolbe Times: We probably need a rebranding exercise.

Richard Rohr: Rebranding – that’s a very good word.

Kolbe Times: Having read much of what you’ve written in the past, I would say that this new book seems very much like a culmination of your teaching, in that you’ve brought together in one book many of the themes that you’ve touched on over the years. For instance, I know you’ve written on the universality theme before – but it feels in this book that you are going deeper, and to new places, and writing with a new urgency.

Richard Rohr: That’s a lovely observation. Thank you. And it’s true, for  instance, that I’ve touched on the theme of universality before. The title of one of my better-selling books was Everything Belongs. This has been the tangent of my life: if something is true, it has to be true everywhere! I’ve said that many times. There can’t be German truth or Methodist truth. If it’s true, it’s true! And we all should be learning how to see it. So you’re right.

instance, that I’ve touched on the theme of universality before. The title of one of my better-selling books was Everything Belongs. This has been the tangent of my life: if something is true, it has to be true everywhere! I’ve said that many times. There can’t be German truth or Methodist truth. If it’s true, it’s true! And we all should be learning how to see it. So you’re right.

But I think what I have now is the advantage and privilege of age. I’m 76. I’ve had a heart attack, and I’m still dealing with cancer. So I know I’m nearing the end. And there’s a wonderful thing that happens – and I’m not the first one to say this, by any means – but you sort of recognize that you need to go for broke, that I hope there is a courage that my old age has given me now. I don’t have to look for any promotions or validation. I can say what my deepest soul believes to be true. But I tried to make it not a personal memoir, but a revelation of the big tradition that kept reappearing. I admit it appeared less and less, especially in the last 500 years, when Christianity became so argumentative, and so provincial, and so ethnic. So I think I just knew I have to say it now, or I’m never going to say it.

And I hope I’m saying it in a way that doesn’t needlessly offend people, or seem like it is unorthodox, because I’m quite concerned about being orthodox. I can’t say these things if this is just my idea. Who am I? “Little Richard from Kansas”, you know?

Unless I’m connecting the dots, unless I’m marking the trajectory of the Hebrew Scriptures, the Christian Scriptures, the world religions, I have no right to speak. I mean that.

Kolbe Times: You’ve been talking to lots of different people lately about your new book, and making a podcast, and recently hosting The Universal Christ Conference in Albuquerque, which was sold out. What are some applications that people have come away with, that you find exciting?

Richard Rohr: I think the most common one, and it sounds rather soft, is hope. I don’t know if you Canadians suffer from it as much as we do, but those terrible books – and I don’t mind calling them that – like Left Behind and The Late Great Planet Earth planted this terrible notion in the last whole generation of North American Christianity that everything is going to hell in a handbag, and that we should actually further the devolution of history because that’s going to make Jesus return. I don’t know how familiar you are with this level of theology, but, you know, it pretty much was taken over by American evangelicalism – and they think this is the Gospel. But in the chapter in my book on the resurrection, which I think is the most important chapter, I write that in fact it’s the exact opposite of the Gospel! That’s fake news, where you make the resurrection of Christ – instead of it being the denouement of history, giving us all a universal hope and meaningful direction – into something else, saying that it’s all ending not with a bang but with a whimper. This has done history an immense disservice.

You Canadians tend to be much healthier than we are in my experience, but the amount of mentally ill and emotionally unstable people I encounter in the American culture…well, it’s like a daily experience, at the supermarket, on the streets. We produce so many unhappy, unhealthy human beings. I can see why so many people here think we have to have our guns, because the whole world seems like such a scary place.

My point is that when it feels like the whole thing is going to hell in a handbag, it is very hard for individual people to find health. They live in an entire enclosure of absurdity – as well as their own individual absurdity, which we all face sooner or later, as I wrote about in my book Falling Upward. But what we’re seeing, at least in America, is that the absurdity is becoming the norm. It’s not the exception; it’s almost what you expect.

If my book in any way can contribute to building a vision of hope, and a culture of hope, then that would be my fondest hope. I think the Gospel was meant to give that to the world. It’s saying, “This is going someplace good!”

But right now, especially with global warming and the terrible state of world politics, and American politics in particular, we’ve got to find a new foundation for optimism – an optimism grounded in the very nature of God.

I’m not talking about an optimism grounded in a philosophy of progress or an understanding of evolution – both of which I agree with, by the way. The fact that Christianity fought against evolution tells a lot about the nature of the Christianity that we have. It wasn’t grounded in the pattern of the resurrection.

Kolbe Times: Do you think that we’re in another stage in history? I can’t help but think about the condition of the world, especially in Germany before World War II, where people wanted something dramatic and new to happen to improve the state of affairs in their country. They were riled up by the difficulties in their situation after World War I, and they were looking for a dramatic form of leadership to change things. It blinded them to what was slowly creeping in to their political and cultural scene. And in the same way, we’re increasingly accepting higher and higher temperatures, like the analogy of the frog in boiling water who doesn’t really notice how hot it’s getting. So how do we respond, when across our society and around the world we have this increasing temperature? I was thinking of the biblical concept that really the only way we can overcome evil is with good.

Richard Rohr: Yes, and of course that biblical concept is true. But it’s not our own “goodness”, in any privatized sense of it, that can ever achieve this. What I’m saying is that the very nature of the grace implanted in everything will achieve it – in spite of us, and in spite of our best attempts to undo it. We keep relying on the philosophy of positive thinking, but we can’t continue thinking that, in and of itself, it’s going to win the day. That’s why  this new book is in many ways a sequel to my last book The Divine Dance, which is about the Trinity, and also about our own transformation. You see, until we get the shape of God right, a philosophy of optimism isn’t going to be enough. God is relationality itself, a relationality of communion and of love. But an awful lot of Christians see God as basically a dictator, or a punitive taskmaster, and it’s very hard to undo that. And we can’t just lay a philosophy of optimism on top of it and hope for the best.

this new book is in many ways a sequel to my last book The Divine Dance, which is about the Trinity, and also about our own transformation. You see, until we get the shape of God right, a philosophy of optimism isn’t going to be enough. God is relationality itself, a relationality of communion and of love. But an awful lot of Christians see God as basically a dictator, or a punitive taskmaster, and it’s very hard to undo that. And we can’t just lay a philosophy of optimism on top of it and hope for the best.

Kolbe Times: Yes, I can see that. We need a much, much larger understanding of God and of the world, which is what’s so exciting about the message in your new book. How has the response been? Have there been any surprises? As I mentioned earlier, you’ve just come out of this big conference which was completely sold out, with 2200 people attending. That’s pretty incredible.

Richard Rohr: And on live streaming, I think it was 3000 more. I’ve got a stack of letters right here, and at this point the response is overwhelmingly positive, happy, excited, congratulatory, grateful.

But, of course, there are those who think I’m a new ager and a pantheist. I make a distinction in the book between pantheism and panentheism. You might not remember. It’s an important distinction. It sounds like just one little, you know, phrase, but pantheism says God is all things; all things are God. That is not orthodox Christian belief. We must maintain the distinction between Creator and creature. And I sure know I didn’t exist in my present form from all eternity. But panentheism says God is in all things. Now, precisely the nature of that probably needs to be worked with, but that’s what we’re saying. An authentic, incarnational Christianity is panentheistic, and it’s called the incarnation. But because we limited the incarnation to the autonomous body of Jesus, we undid most of the salvific work of the Gospel. It became worshipping Jesus, as you’ve probably heard me say, instead of following Jesus, or imitating Jesus. That’s no small point.

Kolbe Times: Yes, I do remember that part in the book, and I think you explained the distinction very clearly. It’s a key section.

Richard Rohr: And I can see why some people’s knee jerk reaction is to say, “That’s heresy.” But honestly, since the book came out, I’ve only gotten a few of those kind of reactions.

Kolbe Times: I’m not surprised that you’ve been receiving mostly very positive reactions. Your book brings such a hope-filled perspective, sorely needed by so many people today.

Richard Rohr: Well, you know, I received something from a reader just this morning, who wrote, “I’m finding it easier now to love my enemies. I realized that the barrier that was there was a self-imposed barrier.” Isn’t that wonderful? At our conference, we used a line from the story at the start of the book by Caryll Houslander – the story we mentioned where she suddenly saw Christ in all the people around her on the train. Later in that story, she writes that we must comfort “Christ who is suffering in sinners”, and even have reverence for them, for they are Christ’s tombs…and Christ in the tomb is potentially the risen Christ. We took that line and made a litany out of it: “Christ in the tomb is still Christ.” In the litany, we stated things like “The drug addict dying in the hospital; Christ in the tomb is still Christ. The political situation in the United States; Christ in the tomb is still Christ.” We kept repeating it with many different statements. And, to be perfectly honest, several recent letters I received have said, “I have found the grace to love Donald Trump.” It got that real for some people.

Kolbe Times: I guess for many people that’s kind of the acid test!

Richard Rohr: At our Living School, here at the Centre for Action and Contemplation, I talk about that marvellous quote from Genesis 1: 26, 27 that says we were created in the image and likeness of God. For almost a three-hundred-year period, in medieval Catholicism, it was almost ‘de rigueur’ for academics to write about the difference between “image” and “likeness”. There were all kind of theories, but here was the consensus at the end: “image” is the objective essence, or you might say “divine DNA”, that every created thing carries from its Creator. That doesn’t come and go. You don’t achieve it by good behaviour. You’ve got it! A Bushman in Africa has it just as much as a Catholic in Quebec. And “likeness” refers to our personal and unique embodiment of that inner divine image. It is our gradual realization of the gift we’ve all been given! We all have the same objective gift, but different ways of saying yes and consenting to it. It’s really brilliant, the problems that this solves. Just because you have the objective image doesn’t mean you’ve appropriated the subjective awareness, behaviour, or attitude, and use it. But – and this is the important part – all people still carry the image. Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler had the image of God in them. We don’t want to say that, but they did. And that’s why we still would have to show their bodies respect. Wow, that asks a lot of us.

But unless we can ask that of ourselves, I don’t think Christianity will ever be a social revolution. It’ll be an ethnic religion, as it has been for most Christians up to now.

Kolbe Times: Do you have plans to write another book?

Richard Rohr: Well, you know, I keep telling the staff here that this is my final book – I have nothing more to say after this. And yet, right now on my home computer, about a block from here, is a monograph in the making…and it won’t be much more than a monograph. I allude to the subject matter in The Universal Christ, but I don’t develop it: namely, Paul’s notion of sin and evil.

In The Universal Christ, I developed how Paul’s notion of salvation is collective, historical, corporate, just as Yahweh made his covenant with the people Israel – not with Moses, not with Noah, not with Abraham, not with David – but through them with the whole nation of Israel. I don’t know how we missed that! The notion of God’s salvation was collective, starting in the Jewish scriptures, and we individualized the whole thing. My point is this: I don’t think I developed enough about how Paul’s notion of evil and sin is also collective.

Let me explain this with a few phrases: “the absurd human condition”; “the tragic state of life”; “the impossible human situation”; “you can live a perfectly good life, and you’re still going to suffer”. I mean, the human condition is tragic! And most human beings who’ve ever lived have been victims in one sense or another. That’s not an exaggeration. By far, the vast majority of human beings have been victims. Now, once we can see that we’re ‘good with one another’s goodness’, then I can’t take pride in Richard being so good. If I’m good, it’s because I had wonderful parents, and I’ve met some very loving people, like yourself, throughout my life.

But just as we’re good with one another’s goodness, we’re also guilty with one another’s guilt; sinful with one another’s sin. And I’m hoping to make this clear in a short monograph that has plenty of foundation. I’m convinced, Bill, that this is what Paul is saying. And once you’re told this, you’ll see it everywhere through Paul’s writing!

Paul is, for me, a spiritual genius of the first magnitude. Paul is not talking about individual nastiness, which is where we tend to put all of our energy – you know, we say to each other and to ourselves, “You should be less selfish!” Well, it’s true, but the reason you are a little bit selfish, and I’m a little bit selfish – more than a little bit – is because I live in a very self-centered culture, where selfishness is idealized, and validated, and rewarded. We are selfish.

Now, I’m not trying to take away the motivation for individual morality or virtue. But I am saying that a lot of the negative self-image that I’ve had to deal with, working with people in prison and in my regular retreat work, is individuals trying to carry the burden of sin by themselves. They say, “I’m a bad person.”

When I started working with teenagers in a Boys’ High School in Cincinnati in 1970, there were so many boys, one after another, who just seemed to hate themselves. These were all middle class, quasi-successful white boys for the most part, but they all seemed to think that they were hopeless, and no good. I think the lone individual is far too insecure and small to carry the burden of sin on his or her own. It’s we who are sinful. And, as I’m reminded every Easter, that is what Jesus was stating on the cross. He was telling us, “I am in solidarity with the tragic human situation.” Wow, that’s a good message, because if Jesus can be in solidarity with human faults, human guilt, human failure, human sin, then I can be as well. I don’t have to keep trying to figure out who are the good guys and who are the bad guys. As Paul says several times in Romans, “we have all sinned, and we have all fallen short of the glory of God.” That is extremely liberating! We start to see that we are all in this together, and that it is just as difficult for everybody else. So please pray, Bill, if I’m supposed to write about this, that I can do it.

Kolbe Times: We’ll be praying for you. You have some really great insights that need to be shared. As I think about it, I see how we have a very strong reluctance to recognize our collective sin. We don’t want to admit that we’re part of the bigger problem, and we’re in fact party to it.

Richard Rohr: Yes. But we’re all contributing. We’re complicit. And instead of Christians trying to prove that they’re innocent, we have Jesus accepting the role of the guilty! His actions are a complete reverse of the Christianity I was raised in – we were all trying to make ourselves innocent. And that just doesn’t get you anywhere, except pretence and denial and projection.

Kolbe Times: What I think you’re talking about is a collective repentance.

Richard Rohr: That’s true, yes. When I can own that we’re all in this together, I can stop the game of comparing and competing. We start to see that we’re all struggling, and we can each own our piece of the pie and say, “Let’s all own this together.” That might mean encouraging one other to live a simpler life, a life that is less destructive of the planet, less consumer-oriented – very Franciscan values, really.

Kolbe Times: That’s great advice to end on. It’s been wonderful talking to you, and we’re so excited about your new book. Thank you very much for spending time with us today.

Kolbe Times: That’s great advice to end on. It’s been wonderful talking to you, and we’re so excited about your new book. Thank you very much for spending time with us today.

Richard Rohr: Well, talking with you today has been a delightful gift for me as well. Meeting you both has made me very happy.

Photos courtesy of The Center for Action and Contemplation

Richard Rohr is a very nice guy, and his ideas about loving and accepting each other are spot on (and not as new as he seems to think) but his theology is off-kilter.

The birth of Jesus 2000 years ago was THE incarnation. The word became flesh and dwelt among us. God made everything the way he wanted it, so we can recognize God in his handiwork, just as we can see Van Gogh in his paintings or hear Bach in his music. But only by having a relationship with Jesus, the historical human being, can we experience direct contact, even union, with God the Father.

Hi Daniel,

John’s Gospel Chapter 1 says In the beginning was the Word; the Word was with God and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things came to be not one thing had its being but through him.