Cheryl Bear is a singer/songwriter, storyteller and teacher. She has spent many years visiting Indigenous communities in Canada and the U.S., sharing her songs and stories. As well, she has become a sought-after speaker at workshops, churches and conferences, raising awareness and understanding of First Nations’ issues.

Cheryl has won numerous awards for her music, which brings alive the joys and sorrows of Indigenous life through story and song. She has released three albums: Cheryl Bear (self titled), The Good Road, and A’BA. Her highly-acclaimed albums have received three Indigenous People’s Choice music awards, two Covenant Awards and a Native American Music Award.

Cheryl has an earned Doctorate from The King’s University in Los Angeles, and a Master of Divinity degree from Regent College in Vancouver, B.C. She is one of the founding board members of the North American Indigenous Institute of Theological Studies (NAIITS), and is also an Associate Professor at Regent College.

Kolbe Times recently had a chance to catch up with Cheryl, and learn more about her life, her faith, and her passion for her people.

Kolbe Times: Tell us a little about your early years, your parents, and some of your experiences growing up.

Cheryl Bear: My mother is an Indigenous woman from the Nadleh Whut’en First Nation community, which is about an hour and a half northwest of Prince George, B.C. My mom went to the Lejac Residential School when she was a child. She met my dad when they were both working up there. Dad emigrated to Canada from Germany in 1968. After my mom and dad were married, they moved to Prince George. Moving from the reserve to a town where she was surrounded by non-native people was quite a culture shock for my mother. She learned how to adapt, but it wasn’t easy. She became a Christian during those early years in Prince George, and my whole family attended a Catholic Church. As I was growing up, we all became quite involved in the Catholic charismatic movement. They held meetings that were quite informal, with Bible studies, prayer times and music with guitars – we enjoyed it very much. I remember that one of the big draws for me were the donuts. There was a guy that everyone called “John the Baker” who used to go to the meetings, and he made the best glazed donuts on the planet!

Because my mom had quite a dramatic conversion to Christianity, and it gave her such peace, she wanted to share what she’d discovered with her people back on the reserve. So she started taking trips back there and holding prayer meetings. I remember going with her and hearing the elders sing in the Catholic Church on the reserve. They had high, beautiful voices, and they would sing in our language – the Dakelh language. I had such a good feeling when I listened to them – it’s hard to describe but it’s a strong memory. We made many, many trips there, and my whole family would all get together at Grampa’s house, and we’d just relax. It always felt like home. I’ve always felt drawn back there, by a strong connection to the people of Nadleh Whut’en, and to the land itself.

Audio of “Story” from Cheryl’s CD The Good Road:

Cheryl Bear: “This story was inspired by Pilgrim’s Progress, and also helped me deal with my uncle’s death, who drowned in the Nadleh River when I was about six years old. For many years, my uncle’s death marked me. Writing this story was part of my healing.”

Kolbe Times: Has singing and performing always been a part of your life?

Cheryl Bear: After my mom became a Christian we were always singing. She had an old beat-up guitar lying around the house, and I decided that I wanted to learn to play it. She told me to learn on the old guitar, and if I stuck with it she’d buy me a new one. So I basically learned by taking that old guitar to the Christian Life Centre in Prince George, and when they played guitars and sang, I’d sit in the front row and try to follow along. And when I was a little older, maybe 14, I started to sing more, and I kept up my guitar-playing, too. I’ve always loved to sing. I think partly because there are so many wonderful singers in my Nadleh community – many of them far more talented than me.

The songwriting came later, when I was working with Indigenous people in Vancouver’s inner city. We started Vancouver Foursquare “Street Church” in the downtown eastside neighbourhood – one of the poorest neighbourhoods in Canada. The first song I ever wrote was after I met Richard Twiss. He’s a Lakota/Sioux from the U.S., and he and his wife Katherine founded the Wiconi Ministry, which is a great organization. They provide all kinds of practical and spiritual support to Indigenous peoples and communities. I was the worship leader at an event that he was speaking at, and I was singing typical church songs with my worship team. Richard came up to me afterwards and said how nice it was to see native people leading worship in church…but then he added, “Why do we always have to sing other people’s songs? We should be writing our own songs, and singing them our own way.” Well, that got me thinking. I said to my team, “You know what, I’m going to write a song.” So later we were reading some Scripture, and that night I wrote music to the Scripture we had been reading. Then we sang the piece the next day, when Richard was speaking again, and he came up to me later and said, “That’s a great song! But why aren’t you using hand drums and other native instruments?” I was like, “Aaaah! This guy is so hard to please!” But I realized that he had made a very good point. So, just by virtue of him asking me these questions, I started writing songs. And the next song I wrote was a doxology, and I called it Drum Doxology because I added drums to it. That was a turning point for me, and for my music. I recorded my first CD in 2005, and Drum Doxology is one of the songs on that CD.

The songwriting came later, when I was working with Indigenous people in Vancouver’s inner city. We started Vancouver Foursquare “Street Church” in the downtown eastside neighbourhood – one of the poorest neighbourhoods in Canada. The first song I ever wrote was after I met Richard Twiss. He’s a Lakota/Sioux from the U.S., and he and his wife Katherine founded the Wiconi Ministry, which is a great organization. They provide all kinds of practical and spiritual support to Indigenous peoples and communities. I was the worship leader at an event that he was speaking at, and I was singing typical church songs with my worship team. Richard came up to me afterwards and said how nice it was to see native people leading worship in church…but then he added, “Why do we always have to sing other people’s songs? We should be writing our own songs, and singing them our own way.” Well, that got me thinking. I said to my team, “You know what, I’m going to write a song.” So later we were reading some Scripture, and that night I wrote music to the Scripture we had been reading. Then we sang the piece the next day, when Richard was speaking again, and he came up to me later and said, “That’s a great song! But why aren’t you using hand drums and other native instruments?” I was like, “Aaaah! This guy is so hard to please!” But I realized that he had made a very good point. So, just by virtue of him asking me these questions, I started writing songs. And the next song I wrote was a doxology, and I called it Drum Doxology because I added drums to it. That was a turning point for me, and for my music. I recorded my first CD in 2005, and Drum Doxology is one of the songs on that CD.

Kolbe Times: As well as being known for your music, you are a widely travelled and respected teacher, pastor and author – and a strong voice in Canada on behalf of Indigenous peoples. I’m sure some of that comes naturally, but tell us a bit about your educational background, getting your Bachelor of Arts, and then a Master of Divinity at Regent College and a Doctorate of Ministry from The King’s College in Los Angeles.

Cheryl Bear: You know, I was the only First Nations student in every one of those programs! It was definitely tough at times. The academic world sometimes can clash with Indigenous values. For instance, the whole concept of debating and refuting and having quick answers was very challenging. The Indigenous people like to listen and be silent and think about what someone has said to them. Only after that time of quiet reflection will they formulate a response. And all that is largely unacceptable in the post secondary world – silence is not valued in debate or discussion! So I had some problems in the classes. But I gained a tremendous amount from those experiences, and I still love Regent College very much. As an associate professor there, I help them with any programs to do with Indigenous people.

Kolbe Times: Your doctoral work ended up as a book called Introduction to First Nations Ministry, which presents First Nations values, worldview, beliefs and practices. It seems like a really important bridge-building resource. How did that come about?

Cheryl Bear: It came out of working with pastors and leaders who asked me a lot of questions, or sometimes just made comments that showed their lack of understanding about Indigenous people. Don’t get me wrong – most people don’t mean to be hurtful, but there’s a lot of misunderstanding and ignorance, unfortunately. So I thought this book might be a good resource for leaders involved in cross-cultural ministry, and for other people as well. I remember one time a Christian leader asked me, “Are there others like you?” I remember thinking, “You’ve got to be kidding me.” I mean, what kind of a question is that, and what does it imply? But I want to give people the benefit of the doubt – though believe me, I’ve had my days where I’ve stormed around angry as hell, because of some comment, or someone making an assumption, or rejecting me because of the colour of my skin. At the same time, I want to be able to create a safe place where people can ask dumb questions, and where I can help, and raise their awareness a little. I think that once we know more about each other, we can start walking together.

Cheryl Bear: It came out of working with pastors and leaders who asked me a lot of questions, or sometimes just made comments that showed their lack of understanding about Indigenous people. Don’t get me wrong – most people don’t mean to be hurtful, but there’s a lot of misunderstanding and ignorance, unfortunately. So I thought this book might be a good resource for leaders involved in cross-cultural ministry, and for other people as well. I remember one time a Christian leader asked me, “Are there others like you?” I remember thinking, “You’ve got to be kidding me.” I mean, what kind of a question is that, and what does it imply? But I want to give people the benefit of the doubt – though believe me, I’ve had my days where I’ve stormed around angry as hell, because of some comment, or someone making an assumption, or rejecting me because of the colour of my skin. At the same time, I want to be able to create a safe place where people can ask dumb questions, and where I can help, and raise their awareness a little. I think that once we know more about each other, we can start walking together.

Kolbe Times: It’s so easy to develop distorted preconceptions, and then start making hurtful and damaging assumptions.

Cheryl Bear: That’s exactly what motivates me. One thing I’ve been thinking about recently is how at church we’re always looking for common ground. People say, “Okay, we’re all Christians, so let’s drop our identities and just be Christians – let’s not worry about differences.” And what that means is the dominant culture gets to rest easy, and determine the style of church, but everyone else who goes there has to just accept how the church is being run. When we say, “Let’s focus on our common identity in Christ”, sometimes that means, “Let’s stay comfortable.” I love challenging people in that area. I like to say, “Let’s talk about our differences! Let’s explore that a little, for a change.” It’s so much richer, I think, to learn about one another’s differences and to respect them and enjoy them. But whenever we think about our differences we think about conflict, and we want to avoid conflict. The truth is that it’s often by going through conflict, and having the courage to risk being a little uncomfortable, that we learn and grow.

Here’s an example of something giving the wrong impression. Silence and humility are very important values in Indigenous culture. Plus, we’ve been silenced so many times throughout history, through harsh, harsh experiences. So now, people think we’re stupid because we don’t speak up – but I know how witty and wise and funny and smart Indigenous people are. Once you know that and see that and understand that, you gain a very different impression. It’s a shame, but First Nations are looked at as having no initiative or leadership incentive. That’s so far from the truth; we have so many wonderful leaders.

Here’s an example of something giving the wrong impression. Silence and humility are very important values in Indigenous culture. Plus, we’ve been silenced so many times throughout history, through harsh, harsh experiences. So now, people think we’re stupid because we don’t speak up – but I know how witty and wise and funny and smart Indigenous people are. Once you know that and see that and understand that, you gain a very different impression. It’s a shame, but First Nations are looked at as having no initiative or leadership incentive. That’s so far from the truth; we have so many wonderful leaders.

Once, when I was visiting a First Nations community, someone said, “Our chief and two hereditary chiefs are here.” I smiled, walked to the back row of the church where some people were sitting, and said, “The chiefs are always sitting in the back row, so you must be the chiefs!” I was right, and they all laughed. It is our culture to honour the chiefs and ask them to come up and say some good words; they knew they did not need to push themselves forward. That’s our way, but because of it we get overlooked.

Kolbe Times: You also have been busy visiting First Nations communities and sharing your music and your stories – and also bringing the Gospel story in a way that makes sense to indigenous peoples. Tell us a bit about that.

Cheryl Bear: Yes, I’ve been to over 600 Indigenous communities now, across Canada and the U.S. The Gospel story is the most beautiful story that I’ve heard in my life – how the Creator loves us so much that He sent his one and only Son, so that whoever believes in Him will have life forever. There’s such power in those words! It’s a story of reconciliation and love, and that love is a free gift. Yet for the Indigenous people the story was never given as a gift. It was used as a tool or a weapon of assimilation. Native people have heard the Gospel for four hundred years. Now they need to hear it in an Indigenous way, in a good way. We use native instruments and music, and we retell the great story of Jesus.

Cheryl Bear: Yes, I’ve been to over 600 Indigenous communities now, across Canada and the U.S. The Gospel story is the most beautiful story that I’ve heard in my life – how the Creator loves us so much that He sent his one and only Son, so that whoever believes in Him will have life forever. There’s such power in those words! It’s a story of reconciliation and love, and that love is a free gift. Yet for the Indigenous people the story was never given as a gift. It was used as a tool or a weapon of assimilation. Native people have heard the Gospel for four hundred years. Now they need to hear it in an Indigenous way, in a good way. We use native instruments and music, and we retell the great story of Jesus.

If you listen to stories about the residential schools at the Truth and Reconciliation Hearings, you’ll soon begin to realize that those schools were absolutely traumatizing for the Indigenous people. I recently was sitting with a friend after a residential school hearing, who had shared her testimony in front of an adjudicator. She had to repeat her story three times. We sat and cried and cried together, because it is so hard to tell those stories. When I hear about such brokenness, I wonder how we can begin to heal some of these things. Many of our people need trauma therapy and grief counselling. The grief is huge in Indigenous communities.

Kolbe Times: It’s so important for all Canadians to hear these stories – to know about these dark parts of our history. Maybe they can help us move beyond stereotypes and false assumptions.

Cheryl Bear: Exactly. First Nations people in Canada have known about the residential schools for a long time, because they are part of so many of our family histories – but non-native Canadians have only been hearing these stories in the last few years.

Kolbe Times: And now, after all the travelling you’ve done, you are spending more time in your own community of Nadleh Whut’en.

Cheryl Bear: Yes, and it’s been such a joy to be back there, living closer with my own people and focusing on helping my community. I was first elected as a band councillor in 2014, and then was re-elected last spring. I’m really loving it.

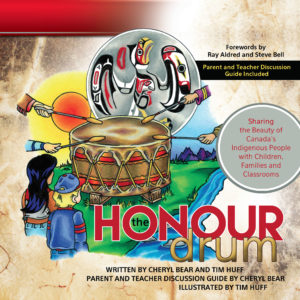

Kolbe Times: Plus, you’ve been working on a new project – a book for children, parents and teachers that you co-wrote with Tim Huff. It’s called The Honour Drum: Sharing the Beauty of Canada’s Indigenous People with Children, Families and Classrooms. What is the story behind this book?

Cheryl Bear: All of my work raising awareness about the Indigenous worldview has been simplified and made very succinct in the few pages of this children’s book, and in the teachers’ guide. Tim Huff and I have been friends for a long time. We first met at a Roundtable on Poverty and Homelessness organized by the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, which brought about thirty people together from across Canada who had a passion for inner city ministry. I really connected with the group, and Tim was one of them. He has worked with poor and marginalized youth and adults in Toronto for decades, and has also written a number of books. Tim is a very talented storyteller and artist, with a gift for awakening your heart to issues that you might never have thought about before. One of his best selling books is called The Cardboard Shack Beneath the Bridge: Helping Children Understand Homelessness. We began talking about the differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada. And as we kept exploring the topic, he began to talk about how great it would be to write a children’s book together. One evening over coffee he asked me what would be some of the important things I’d like to tell Canadians about Indigenous people and their way of life. Well, I started naming things off, and those became the different “stanzas” in the book.

Cheryl Bear: All of my work raising awareness about the Indigenous worldview has been simplified and made very succinct in the few pages of this children’s book, and in the teachers’ guide. Tim Huff and I have been friends for a long time. We first met at a Roundtable on Poverty and Homelessness organized by the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, which brought about thirty people together from across Canada who had a passion for inner city ministry. I really connected with the group, and Tim was one of them. He has worked with poor and marginalized youth and adults in Toronto for decades, and has also written a number of books. Tim is a very talented storyteller and artist, with a gift for awakening your heart to issues that you might never have thought about before. One of his best selling books is called The Cardboard Shack Beneath the Bridge: Helping Children Understand Homelessness. We began talking about the differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada. And as we kept exploring the topic, he began to talk about how great it would be to write a children’s book together. One evening over coffee he asked me what would be some of the important things I’d like to tell Canadians about Indigenous people and their way of life. Well, I started naming things off, and those became the different “stanzas” in the book.

That began a three-year period – this long back-and-forth conversation with ideas for the book. We met whenever we could, in different cities across Canada. Tim also did the illustrations. Lots of times our conversations were difficult to navigate, as we talked through so many issues and misconceptions about Indigenous culture. But Tim and his wife Diane are such dear friends of mine and the journey was definitely worth it, to walk alongside them and work through all the tricky problems that come along when you put together something like this. I’m so proud of our hard work in this beautiful book, and I pray that it will shed some new light on the truth about the history of Canada for our young people…so we can all move forward together.

For more information about Cheryl Bear, her upcoming events, CDs and books, visit www.cherylbear.com

Follow her on Facebook

All photos courtesy of Cheryl Bear.

Cheryl Bear singing A’BA, the title track from her CD of the same name: