Asta Encounters the Divine in Big Laurel Creek

Asta at Big Laurel Creek. Photo by Gene Hyde

“The dog would remind us of the pleasures of the body with its graceful physicality, and the acuity and rapture of the senses, and the beauty of forest and ocean and rain and our own breath.” -Mary Oliver, “Dog Talk”

Sun soaked and sparkling

Asta somehow knows, sipping

Deep the light-filled creek,

Shimmering, shining,

So numinous below. The

Ripples softly speak

Of this bright altar,

Of this holy flow, of this

Old dog’s raptured glow.

For more of Gene Hyde’s writing and photography, visit Bantering Bibliocrat

If I Can Stop One Heart From Breaking

If I can stop one heart from breaking,

I shall not live in vain;

If I can ease one life the aching,

Or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting robin

Unto his nest again…

I shall not live in vain.

Painting: The First Grief by Daniel Ridgway Knight (1839-1924)

One Light

Photo by Egeni Tcherkasski

A single light can lead you home. One light

is all you need to break the back of night

when darkness seems to weigh more than it has

on all the nights before, and nothing’s as

it was. Bit by bit, the lighter shades

of night you used to trust have faded as

you stopped believing in relief. The dark

goes on forever, and begins right where you are.

But when your eyes can’t guide your steps, you learn

to trust your heart instead. You rise and turn

toward where you need to go, and in the dark

you think you see a glimmer like a star

that wasn’t there until you headed home

through darkness, trusting that a light would come.

From Dana Wildsmith’s poetry collection One Light (Texas Review Press, 2018)

Reprinted with permission.

Sometimes, I Am Startled Out of Myself

like this morning, when the wild geese came squawking,

flapping their rusty hinges, and something about their trek

across the sky made me think about my life, the places

of brokenness, the places of sorrow, the places where grief

has strung me out to dry. And then the geese come calling,

the leader falling back when tired, another taking her place.

Hope is borne on wings. Look at the trees. They turn to gold

for a brief while, then lose it all each November.

Through the cold months, they stand, take the worst

weather has to offer. And still, they put out shy green leaves

come April, come May. The geese glide over the cornfields,

land on the pond with its sedges and reeds.

You do not have to be wise. Even a goose knows how to find

shelter, where the corn still lies in the stubble and dried stalks.

All we do is pass through here, the best way we can.

They stitch up the sky, and it is whole again.

From Radiance by Barbara Crooker (Word Press, 2005)

Photo by Melanie Lolame

With Hope in My Heart: Musings of a Spirited Psychiatrist by François Mai

Published by Friesen Press, Canada; 2022

Review by Laura Locke

With Hope in My Heart: Musings of a Spirited Psychiatrist (Friesen Press, Canada; 2022) is a rewarding account of a life filled with remarkable achievements, as well as tragedies, missed opportunities, and many bends in the road. In looking back at his life, author François Mai isn’t afraid to reveal not only his successes, but also, with admirable humility and openness, his faults. He also helps us recognize that it is by facing and admitting our mistakes that we can grow, both personally and as a society. Throughout the twists and turns of his life story, readers get to know his interesting family – including ancestors in his family tree. The many photographs sprinkled throughout the book add more insight. In Mai’s memories and reflections, we are also rewarded with examples of how to live life fully and generously.

With Hope in My Heart: Musings of a Spirited Psychiatrist (Friesen Press, Canada; 2022) is a rewarding account of a life filled with remarkable achievements, as well as tragedies, missed opportunities, and many bends in the road. In looking back at his life, author François Mai isn’t afraid to reveal not only his successes, but also, with admirable humility and openness, his faults. He also helps us recognize that it is by facing and admitting our mistakes that we can grow, both personally and as a society. Throughout the twists and turns of his life story, readers get to know his interesting family – including ancestors in his family tree. The many photographs sprinkled throughout the book add more insight. In Mai’s memories and reflections, we are also rewarded with examples of how to live life fully and generously.

Mai grew up in South Africa during the Apartheid era. As a history buff, I was fascinated by his accounts of South Africa’s early years, the growth and reality of apartheid, and the stormy journey toward becoming the country it is today. Tales of his childhood, and of the beauty of his childhood home, are both enlightening and captivating. Mai also writes in detail about his parents’ immigration from France, and the ongoing issues that this raised for the whole family. We learn about his mother’s talent as a professional musician and how he inherited her love of classical music – and also about his complicated relationship with his father.

Mai became an activist opposing apartheid. He writes, “The illegalities and immorality of apartheid also had a major effect on my career plans and my philosophy. They caused me to identify strongly with the poor and the marginalized in our society, and few are more marginalized than those with chronic psychiatric illness. My experience as an activist in the political maelstrom that was South Africa became a founding factor that influenced my decision to follow a career path in psychiatry.” (pg. 6)

We can see the weaving of many threads coming together, including his Christian faith as a member of the Catholic Church. He grew to believe that hope is an essential tenet of Christianity, and is also an essential ingredient of life. The details of his path to becoming a psychiatrist include many ups and downs, and readers will appreciate his vividly-written stories of the effort, triumphs and disappointments along the way. I also enjoyed Mai’s description of the history of psychiatry, with stories of many of the colourful characters who were part of that history.

One bright light at the beginning of his medical education was his courtship of a pretty young nurse, Sarie, who became his wife. Mai earned his medical degree in 1956 at the University of Cape Town and completed psychiatric residencies in England and Scotland, plus a 12-month fellowship in New York. Mai and his family moved to Canada in 1972, where he continues to reside. His career stretched over fifty years, and throughout his life Mai has also enjoyed cycling and swimming, as well as playing piano and organ. In the latter part of the book, he eloquently describes the joys and challenges of his retirement years.

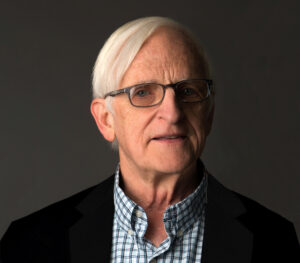

Dr. François Mai

In the book, Mai is not afraid to write about his aversion to some tenets of the Catholic Church, nor is he averse to criticizing the field of psychiatry, especially in the area of diagnostic classification systems. He also has harsh words for some of the actions of the pharmaceutical industry. However, we also read about his admiration and respect for many figures throughout the history of psychiatry, as well as snapshots of his own personal mentors and many friends who touched his life. As well, Mai goes into loving detail about life with his adventurous and patient wife and their four sons.

I also appreciated his thoughts on spirituality, such as this passage about the aftermath of the death of their two-month-old son, Paul, of SIDS in 1965:

“Suffering has meaning only if it is placed in a spiritual context. God has allowed suffering because there is evil in the world. He has allowed the evil, not created it. Evil and suffering test us, and there can be ultimate benefit or reward through spiritual growth, maturation, or heavenly repose. Christ gave us his example by his awful death on the Cross: “Forgive them, Lord, for they know not what they do.” I believe it is not possible to understand pain and evil without giving them a spiritual dimension. As Paul Bunyan said in The Pilgrim’s Progress, “In times of affliction we commonly meet with the sweetest experiences of the love of God.” These factors, and the promise of meeting Paul again in the afterlife, enabled me to come to terms with the hurt and bereft feeling of his death. It was an acid test of my faith.” (pg. 117)

Written from the heart, this book is indeed a gift of hope.

—

François Mai is also the author of Diagnosing Genius: The Life and Death of Beethoven (McGill/Queen’s University Press, 2007) and the novel Father, Unknown, set during and after the French Revolution (Austin Macauley Publishers, 2017). Since 1966, he has written 115 articles, the majority in peer-reviewed medical journals.

Visit François Mai’s website.

Photo of François Mai by Marilyn Mikkelsen.

A Moment of Happiness

A moment of happiness,

you and I sitting on the verandah,

apparently two, but one in soul, you and I.

We feel the flowing water of life here,

you and I, with the garden’s beauty

and the birds singing.

The stars will be watching us,

and we will show them

what it is to be a thin crescent moon.

You and I unselfed, will be together,

indifferent to idle speculation, you and I.

The parrots of heaven will be cracking sugar

as we laugh together, you and I.

In one form upon this earth,

and in another form in a timeless sweet land.

(translated by Coleman Barks; photo by Evgeniya Ivanova)

The Reinvention of Work: A New Vision of Livelihood for Our Time by Matthew Fox

Harper Collins Publishers, 1994

Review by Bill Locke

“How many of us can really say that our work life is in balance with our personal life – that our values and desires are reflected in our daily vocation, that our personal life and professional life are integrated, or that we find satisfaction, not a crushing defeat of the spirit, in our workday existence? According to most polls and reports, very few of us do.”1

The above quote sounds like a contemporary comment. Actually, it was written in 1994. Recent Gallup polls indicate that 60% of citizens report being emotionally detached at work, and 19% being miserable.2 As well, many feel that their work-life balance is out of whack. After going through lockdowns during the pandemic, spending time away from work or working from home, many in Western countries are now questioning the very place of work in their lives. Dissatisfaction, boredom, feeling overworked or having trouble finding fulfilling work are all common complaints. According to author, theologian and Episcopal priest Matthew Fox in his book The Reinvention of Work: A New Vision of Livelihood for Our Time, it’s because we have removed the sacred from our day-to-day existence. This is not to say that a sacred life will be easy. The Sufi sage Rumi exhorts us to “work in the invisible world at least as hard as you do in the visible.”3

The above quote sounds like a contemporary comment. Actually, it was written in 1994. Recent Gallup polls indicate that 60% of citizens report being emotionally detached at work, and 19% being miserable.2 As well, many feel that their work-life balance is out of whack. After going through lockdowns during the pandemic, spending time away from work or working from home, many in Western countries are now questioning the very place of work in their lives. Dissatisfaction, boredom, feeling overworked or having trouble finding fulfilling work are all common complaints. According to author, theologian and Episcopal priest Matthew Fox in his book The Reinvention of Work: A New Vision of Livelihood for Our Time, it’s because we have removed the sacred from our day-to-day existence. This is not to say that a sacred life will be easy. The Sufi sage Rumi exhorts us to “work in the invisible world at least as hard as you do in the visible.”3

Rev. Dr. Matthew Fox, in his positively disruptive way, proposes an answer: reinventing our notion of “work”. Building on a wealth of thinking by muses and mystics, prophets and philosophers, he takes a whole new and yet old way to look at our labours. It is as if to answer the prayer of Thomas Aquinas, who pleaded:

“Grant me, O Lord my God, a mind to know you, a heart to seek you, wisdom to find you, conduct pleasing to you, faithful perseverance in waiting for you, and a hope of finally embracing you.”

Fox calls on his readers to restore the fullest meaning of work, to leave behind damaging views of so-called meaningless jobs, and to share in the vision of going beyond our personal and professional aspirations to a place of “soul work.”

Rev. Dr. Matthew Fox

He brilliantly reconnects work to spiritual life, reminding us that our feelings of imbalance often emanate from within ourselves. Fox encourages each of us to look at our lives, not from the point of view of our jobs or careers or workplaces, but to go deeper, seeing what is happening to us at our core:

“Life and livelihood ought not to be separated but to flow from the same source, which is Spirit, for both life and livelihood are about Spirit. Spirit means life, and both life and livelihood are about living in-depth, living with meaning, purpose, joy and a sense of contributing to the greater community. A spirituality of work is about bringing life and livelihood back together again.”4

As E.F. Schumacher (author of the bestseller Small is Beautiful; 2011) wrote in his book Good Work:

“Everywhere, people ask: ‘What can I actually “do”?’ The answer is as simple as it is disconcerting: We can, each of us, work to put our own inner house in order.”5

Looking back to the Industrial Revolution, Fox tells us the model of work began there. It’s a model which we still use. It is one of increasingly rapid output with workers as cogs in a great production wheel. We should be connected, yes, but not to the ‘wheel’ so much as to one another. Fox quotes economist Hazel Henderson, one of the authors of Redefining Wealth and Progress6, who characterizes the industrial economic approach as having “unchecked production, consumption and continuous economic growth”. Fox seeks to transform that approach, envisioning a future focused on the ‘infinite’:

“This newly found sense of spirituality will in turn end the cycle of avarice on which modern consumer economics is based; we will find our quest for the infinite or for Spirit in places that truly satisfy.7

The biggest wheel of work, Fox writes, is the universe, which is best seen through cosmology:

A cosmological perspective on work can show us that all creatures in the universe have work – the galaxies and stars, trees and dolphins, grass and mountain goats, forests and clouds – all are working. The only ones out of work are human beings. The very fact that our species has invented unemployment ought to give us pause. Unemployment is not natural.8

Fox stands back from the nine-to-five existence to tell us what employment is really about: God’s work in us and through us. He beautifully explains that the Spirit who ‘hovered over the waters’ at the beginning of the world is committed to a work of co-creation with us.

For perspective, Fox also looks through the lens of the prophets and mystics. Meister Eckhart, undoubtedly his favorite mystic, tells us that the Spirit is not only water, but also wind and fire.

“Indeed, it is the wind that fans the ‘spark of the soul’ that burns incessantly in all of us. This spark is hidden, something like the original outbreak of goodness, something like a brilliant light that incessantly gleams. … This fire is nothing else than the Holy Spirit.9

Also calling on the wisdom of Hildegard of Bingen, Thomas Aquinas, Rumi, Bhagavad Gita, and other diverse sources of cosmological wisdom, Fox encourages us to move away from a fixation on the materialistic ethos of the industrial revolution. He makes no bones about it – we should get on with the dream and the doing of something much bigger with our lives.

According to Fox, we must change our paradigm about the way we work, how we think and talk about work, our investment in our jobs, and for that matter, our external existence. Instead of focusing exclusively on the externals, we must also do the inner work, to get on with expressing who we really are. This takes us to the deep level of consciousness and sometimes comes across as ‘quantum woo-woo’. But it is feasible and do-able, Fox writes. If we strive to keep our lives authentic – embedding ourselves in the value of relationships, pouring ourselves out for others, facing our fears, honouring our inspirations, and doing what we feel is right – we can be part of something transcendent:

“We become real when our work joins the Great Work. We become real when our inner work becomes work in the world; when our creativity, born of deep attention to both enchantment and nothingness, serves the cause of transformation, healing, and celebrating.”10

I was captivated by the first two-thirds of the book especially. There, Fox reframes and unpacks the theology of work. The last third of the book is packed with creative ways to enhance work in the realms of material production, business, health, politics, academia, youth, art, and science. He questions the various professions in these fields, seeking a renewed focus on social justice, renewal and basic civility. As an example, he describes a successful experiment by the Sandinistas in Nicaragua that sent literate teenagers into villages and farm communities to teach illiterate adults. In Fox’s words, the results were amazing.

As imaginative and fascinating as these final chapters can be, I found them occasionally to be somewhat pie-in-the-sky. Fox defers to Rolf Osterberg, CEO of one of Sweden’s biggest film companies, who claims that:

“Work, as every other aspect of life, is a process through which we acquire experiences … the primary purpose of a company is to serve as an arena for the personal development of those working in the company. The production of goods and services and the making of profits are by-products.”11

If only it were so.

Though Fox wrote this fascinating book almost 30 years ago, I find that he is still ahead of his time. We haven’t shifted our economy enough in the directions he explores. As Fox himself argues, instead of shining the spotlight on our output or how fast we can turn the wheel of material production, we should be paying more attention to our role in effecting joy and peace for ourselves, and those around us.

The Reinvention of Work: A New Vision of Livelihood for Our Time may be timelier now more than ever. I recommend it highly; consider finding a copy to examine, enjoy, and employ.

Plant a Garden

Photo by Anton Deev

If your purse no longer bulges

and you’ve lost your golden treasure,

If at times you think you’re lonely

and have hungry grown for pleasure,

Don’t sit by your hearth and grumble,

don’t let mind and spirit harden.

If it’s thrills of joy you wish for

get to work and plant a garden!

If it’s drama that you sigh for,

plant a garden and you’ll get it.

You will know the thrill of battle

fighting foes that will beset it.

If you long for entertainment and

for pageantry most glowing,

Plant a garden and this summer spend

your time with green things growing.

If it’s comradeship you sigh for,

learn the fellowship of daisies.

You will come to know your neighbor

by the blossoms that he raises;

If you’d get away from boredom

and find new delights to look for,

Learn the joy of budding pansies

which you’ve kept a special nook for.

If you ever think of dying

and you fear to wake tomorrow;

Plant a garden! It will cure you

of your melancholy sorrow.

Once you’ve learned to know peonies,

petunias and roses,

You will find every morning

some new happiness discloses.

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson

Published in Canada by Anchor Canada, a division of Penguin Random House, 2021

Review by Laura Locke

Even though I never studied Science formally at university, I have realized rather late in life that I enjoy challenging my brain by learning about scientific principles, and discoveries throughout history in biology, chemistry and physics. This new interest of mine seems a bit odd to my family and friends, but there it is. I’m a big fan of the science documentaries presented by the Iraqi-British theoretical physicist Jim Al-Khalili (streaming on Prime Video), and I also love reading biographies of famous scientists. When I recently found out that bestselling author Bill Bryson had written a new book all about the intricacies of the human body, I couldn’t wait to get my hands on it.

Bill Bryson was born in Iowa in 1951, but settled in England in 1977, working in journalism before writing books. His first book, The Palace Under the Alps, And Over 200 Unusual, Unspoiled and Infrequently Visited Spots in 16 European Countries (Congdon & Weed Publishers, 1985) was not one of his most notable, but it led to a prodigious number of other books penned by Bryson, many of which have become bestsellers. Besides his very popular travel books, he has also written books about Shakespeare, his childhood, language, and history. He has, in fact, sold more non-fiction books in the U.K. than any other author, and in 2006 was awarded an OBE for his contribution to literature. Perhaps Bryson’s two most successful books have been The Mother Tongue: English and How It Got That Way (William Morrow Publishers, 1990), which explores the history and eccentricities of the English language, and A Short History of Nearly Everything (Doubleday, 2003), a widely acclaimed book on the history of science, both of which I thoroughly enjoyed. Bryson is known for his ability to make history and science understandable, as well as very entertaining.

His latest book, The Body: A Guide for Occupants, could rightfully be called a ‘tour de force’ because of the sheer amount of intriguing, remarkable, and often bizarre facts about this form we occupy. Bryson draws on the knowledge of dozens of experts, and marvels as much as his readers at the details he discovers about our bodies. I learned more about the thousands of beneficial micro-organisms that live on and in my body than I probably wanted to know, but I also learned about countless other fascinating and rather mind-boggling realities about the human frame. For example, I now know that smell accounts for at least 70% of what we sense as the “flavour” of food … that our amazing hearts beat approximately 100,000 times a day … that every time we breathe, we exhale around 25 sextillion (that’s 2.5 x 1022) molecules of oxygen … and that we grow about 25 feet of hair in our lifetime.

His latest book, The Body: A Guide for Occupants, could rightfully be called a ‘tour de force’ because of the sheer amount of intriguing, remarkable, and often bizarre facts about this form we occupy. Bryson draws on the knowledge of dozens of experts, and marvels as much as his readers at the details he discovers about our bodies. I learned more about the thousands of beneficial micro-organisms that live on and in my body than I probably wanted to know, but I also learned about countless other fascinating and rather mind-boggling realities about the human frame. For example, I now know that smell accounts for at least 70% of what we sense as the “flavour” of food … that our amazing hearts beat approximately 100,000 times a day … that every time we breathe, we exhale around 25 sextillion (that’s 2.5 x 1022) molecules of oxygen … and that we grow about 25 feet of hair in our lifetime.

I also love that Bryson weaves in stories of many doctors, researchers and scientists throughout history who have tried to figure out the why’s and how’s of the workings of our body – sometimes correctly, and more often not. As well, he chronicles the development of many life-saving devices, procedures and medications (such as the X-Ray machine, heart transplants, and antibiotics.)

Bryson includes many particulars about our human body that continue to mystify the experts. Here’s an example, which also shows Bryson’s engaging writing style: In the early 1880s, German surgeon Gustav Simon “removed a diseased kidney from a female patient without having any idea what would happen, and was delighted to discover – as presumably was the patient – that it didn’t kill her. It was the first time that anyone realized that humans can survive with just one kidney. It remains something of a mystery even now as to why we have two kidneys. It is splendid to have a backup, of course, but we don’t get two hearts or livers or brains, so why we have a surplus kidney is a happy imponderable.”1

Bryson has been quoted as saying that he “is not a spiritual person”, and in this book he describes the human journey as a “long and interesting accident, but a pretty glorious one.”2 However, I found his latest book to be personally faith-boosting, and gave me a deeper understanding and appreciation of the wonder of life itself. Each and every one of us is a walking, talking miracle!

- The Body: A Guide for Occupants; pg. 154

- Ibid; pg. 10

When Stretch’d On One’s Bed

When stretch’d on one’s bed

With a fierce-throbbing head,

Which preculdes alike thought or repose,

How little one cares

For the grandest affairs

That may busy the world as it goes!

How little one feels

For the waltzes and reels

Of our Dance-loving friends at a Ball!

How slight one’s concern

To conjecture or learn

What their flounces or hearts may befall.

How little one minds

If a company dines

On the best that the Season affords!

How short is one’s muse

O’er the Sauces and Stews,

Or the Guests, be they Beggars or Lords.

How little the Bells,

Ring they Peels, toll they Knells,

Can attract our attention or Ears!

The Bride may be married,

The Corse may be carried

And touch nor our hopes nor our fears.

Our own bodily pains

Ev’ry faculty chains;

We can feel on no subject besides.

Tis in health and in ease

We the power must seize

For our friends and our souls to provide.

This poem is in the public domain.