Valentine for Ernest Mann

You can’t order a poem like you order a taco.

You can’t order a poem like you order a taco.

Walk up to the counter, say, “I’ll take two”

and expect it to be handed back to you

on a shiny plate.

Still, I like your spirit.

Anyone who says, “Here’s my address,

write me a poem,” deserves something in reply.

So I’ll tell a secret instead:

poems hide. In the bottoms of our shoes,

they are sleeping. They are the shadows

drifting across our ceilings the moment

before we wake up. What we have to do

is live in a way that lets us find them.

Once I knew a man who gave his wife

two skunks for a valentine.

He couldn’t understand why she was crying.

“I thought they had such beautiful eyes.”

And he was serious. He was a serious man

who lived in a serious way. Nothing was ugly

just because the world said so. He really

liked those skunks. So, he re-invented them

as valentines and they became beautiful.

At least, to him. And the poems that had been hiding

in the eyes of skunks for centuries

crawled out and curled up at his feet.

Maybe if we re-invent whatever our lives give us

we find poems. Check your garage, the odd sock

in your drawer, the person you almost like, but not quite.

And let me know.

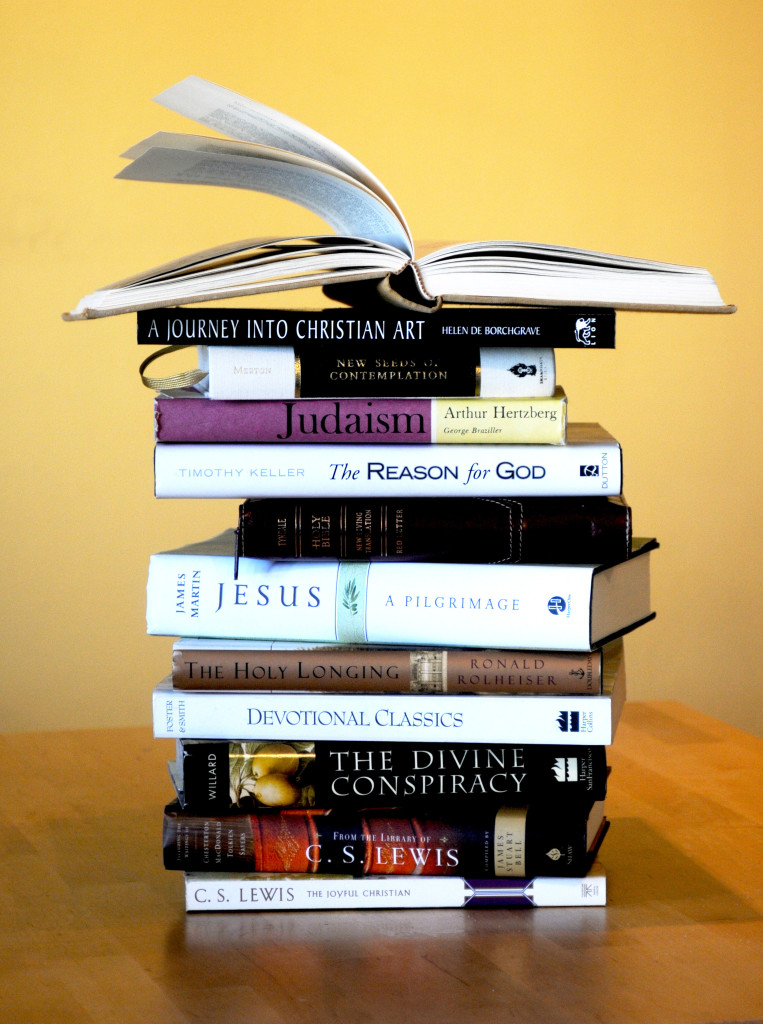

Dr. Gordon Smith: Books That Changed My Life

This is the third article in our series, in which we ask leaders in our faith community to discuss important books in their lives. Past contributors have included Bishop Frederick Henry and Dr. Gerry Turcotte, President of St. Mary’s University.

I grew up within an evangelical spiritual and theological tradition and religious sub-culture that was deeply ambivalent if not actually “anti” the sacraments. If we did anything at all that even looked sacramental, we insisted that it was merely an “ordinance” – that is, “just an symbol”, as we were wont to say – and we further insisted that it had no redeeming value, no grace for the Christian.

Well, a series of books – both fiction and non-fiction – led me to a change of heart and mind, and into a deep appreciation of the sacramental life of the church.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Life Together was influential in my life in so many ways, including the rather intriguing suggestion that each time the community of faith gathers at Table they do so with the Risen Christ as their host. And, further, that the church is actually formed by the simple act of eating together in the presence of Christ.

Then there is the priest – typically referred to as the “whiskey priest” in Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory – who is on the run for his life from Mexican authorities at a time that the church and religious were illegal in Mexico. Whenever he comes to a point of potential escape, crossing a state line, he feels compelled to stop and preside at the Eucharist. And for one coming from my background, I was amazed that the “table” would matter so much – that it would mean so much to one who was called into religious leadership.

Lesslie Newbigin was also an essential voice in my formation as a young adult, and he continues to be as significant a voice as any in my understanding of the church. His book, The Household of God, remains in my life as one of the most formative books when it comes to my appreciation of the vital place of the sacraments and especially the Lord’s Supper in the life and witness of the church. Newbigin is another voice that insisted for me and to me that what makes the church the church is that it gathers at table.

The above books were read in my twenties and thirties. But then, later in life – by then into my forties – I came across the exquisite book, the capstone of them all for me: For the Life of the World, by Alexander Schmemann, a Russian Orthodox priest who was for many years the Dean of St. Vladimir’s Seminary north of New York City. Schmemann writes with winsome power about the efficacy of God in the sacramental actions of the church and of the joy that is found in and through our participation in the Eucharist. Yes, that is precisely the word – joy! My upbringing seemed to assume that the saddest moment of all was this rather sober and solemn approach to the Lord’s Supper that we tacked on to our worship events once a month on the first Sunday of the month. It was an occasional event – not weekly; but more it was not in any way a happy event. No one looked forward to it; everyone viewed it as necessary, perhaps – because Christ had commanded it – but it was hardly a time when we felt any measure of joy! And here I am reading Schmemann who not only speaks of joy as indispensable to human life but also of the Table – the Lord’s Supper – as the very means by which we are being drawn up into the joy of God. I read the book in one sitting.

Since then, several other authors have contributed more insight into the meaning of the Eucharist for me. I have even myself gone on to write a book on the Lord’s Supper (A Holy Meal, Baker Publishers, 2005). But my gratitude to these authors is not merely that I came to write a book on the Eucharist, leaning on their insights, but the way in which they each, in different ways, helped me come to a greater appreciation of Table in the life and witness of the Church. In time I learned that all of this was part of John Wesley’s theology and practice, as is evident in his delightful sermon “The Duty of Constant Communion.” And I began to see references to the sacraments and to the Lord’s Supper in particular in A.W. Tozer, who was so formative in my own tradition.

But that sequence – from Bonhoeffer, to Greene, to Newbigin and eventually to Schmemann – had a deeply formative impact on my life.

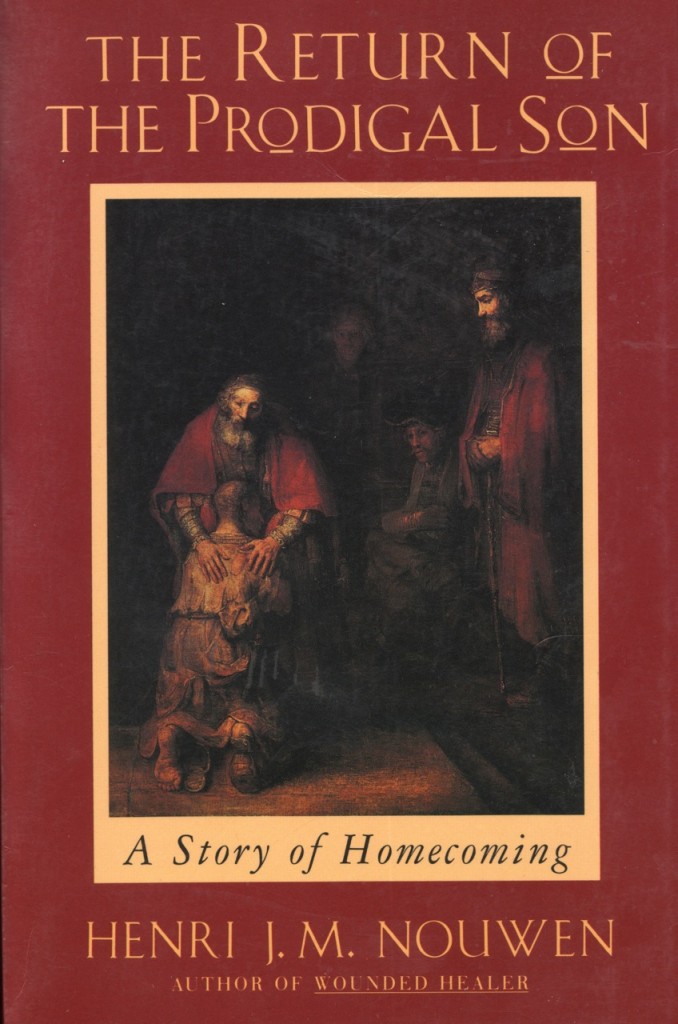

The Return of the Prodigal Son by Henri Nouwen

With the theme of “Mercy” for this issue of Kolbe Times, it seemed the perfect chance for me to read and review The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming by Henri Nouwen. I’ve long been a fan of Nouwen’s books, but somehow this one never made it to my bedside table. Based on Jesus’ powerful parable of a wayward younger son returning home to face his father and older brother found in Luke 15: 11-32, this book is a captivating exploration of forgiveness and restoration.

With the theme of “Mercy” for this issue of Kolbe Times, it seemed the perfect chance for me to read and review The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming by Henri Nouwen. I’ve long been a fan of Nouwen’s books, but somehow this one never made it to my bedside table. Based on Jesus’ powerful parable of a wayward younger son returning home to face his father and older brother found in Luke 15: 11-32, this book is a captivating exploration of forgiveness and restoration.

Henri Nouwen was a Dutch-born priest who studied psychology and theology, and then went on to teach at various universities and theological institutes, including Notre Dame, Yale and Harvard. Nouwen was the author of over forty books, and he often wrote in a disarmingly intimate style, exploring our human need for meaning and intimacy. Nouwen suffered from bouts of depression, and he wasn’t afraid to write about his struggles and his very personal spiritual insights, which is precisely what makes his books so potent and helpful. In an interesting tie to our cover story about the fiftieth anniversary of L’Arche, Nouwen spent his last ten years living and serving at L’Arche Daybreak Community near Toronto, before his sudden death of a heart attack in 1996.

The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming was first published in 1992, but the story told in the book begins ten years earlier. After an exhausting lecture tour across the U.S., Nouwen decided to visit the L’Arche community in Trosly-Breuil, France for a time of rest and to visit his new friend Jean Vanier. While there, he happened to see a poster of the famous painting by Rembrandt entitled The Return of the Prodigal Son. Nouwen writes that his heart leapt when he saw it. He recalls, “The tender embrace of father and son expressed everything I desired at that moment.”

And so began a sometimes painful but very fruitful spiritual adventure, which Nouwen shares with us in this beautifully written book. After seeing the poster, he embarked on an in-depth exploration of the themes in the parable, Rembrandt’s life, the painting itself, and his own self-image. Nouwen not only read all the biographies of Rembrandt and historical studies of the painting that he could find, he also travelled to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia to see the original painting. As is the case with many of his books, Nouwen openly shares the very personal revelations that arose out of his research and mediations. He begins the book by drawing comparisons between the younger son in the parable who flees from his loving home, and his own life:

“Over and over again I have left home. I have fled the hands of blessing and run off to faraway places searching for love. This is the great tragedy of my life, and of the lives of so many I meet on my journey.”

Nouwen later starts to wonder if perhaps he is also much like the elder brother in the parable, and this opens a whole new avenue of exploration and self-reflection. Nouwen does a brilliant analysis of how deeply rooted the “lostness” of the elder brother is, and how hard it is to return home from there. He writes:

“At the very moment I want to speak or act out of my most generous self, I get caught in anger or jealousy. And it seems that just as I want to be most selfless, I find myself obsessed about being loved. Wherever my virtuous self is, there also is the resentful complainer. I am faced with my own true poverty. Can the elder son in me come home?”

In the last third of the book, Nouwen focuses on the father in this parable. He marvels at God’s eagerness to “run to welcome his returning son and fill the heavens with sounds of divine joy.” Nouwen has a surprising and life-changing revelation – that perhaps he is being called to become the father: “I now see that the hands that forgive, console, heal and offer a festive meal must become my own.”

Nouwen does a marvelous job of deconstructing elements of the painting itself – the placement of the characters, the lighting, the symbolism of the clothing, the representation of the father’s hands, the subtle use of colour, the facial expressions. It’s both fascinating and very enriching to get lost with Nouwen in these aspects of the painting, to examine their significance, and to speculate on what Rembrandt might have been trying to convey.

Through his clear and engaging writing style, Nouwen gently enticed me down a path of my own self-reflection. What is Jesus saying to me through this parable? Am I most like the younger son or the older brother? Are there some situations in my life where my hands could become more like the father’s hands? The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming is a both an inspiration and a guide, lighting the way towards a deeper understanding of ourselves, and of our merciful God’s longing to be fully reconciled with each of us.

The Rich and Poor Have This in Common

All these signs of contradiction in my midst

The modern lepers who I refuse to kiss

I cannot deny the mystery that they are blessed

The poorest, wholly set apart from all the rest

Foolishness to the world and to me

Their suffering from which I turn so easily

But it isn’t righteousness I feel

But rather, as I turn the corner, the longing just to kneel

Who is my neighbour? I only start to grasp

When my two folded hands are firmly clasped

In prayer I come dependent before the throne

Naked, or in rags I do not own

Pleading mercy unworthily, like a beggar in the street

Broken and hungry, needing anything to eat

Love takes me in and Mercy shows me grace

As I barely look my own strangers in the face

The double standard between Holy Love and ours

Is the difference between a bystander

And a giving victim bearing scars.

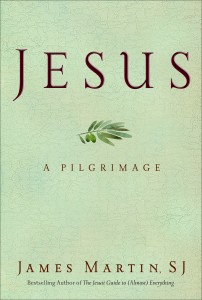

Jesus: A Pilgrimage by Fr. James Martin, SJ

James Martin has succeeded beautifully. He has written a book that can engage both committed Christians and those who know nothing of Jesus. Starting from the conviction that Christ is fully human and at the same time fully divine, Martin fleshes out this startling enigma by revealing a Jesus who ‘sweated and sneezed and scratched’ but who also truly rose from the dead.

The idea for the book came about when Martin decided to go on pilgrimage to the Holy Land. After initial reluctance he went with a Jesuit friend, taking a two-week trip to explore the Gospel stories in the very places where the events are believed to have taken place. The result is an extraordinary, humourous and poignant travelogue – part literature review and part meditation on the meaning of Jesus’ life. Martin weaves his story between contemporary Israel and Palestine and the Biblical past, from the concrete to the transcendent. What stays with me particularly is the description of chatty passengers on the Number 21 bus to Bethlehem juxtaposed with the meditation of the Gospel stories commemorated on that very ground.

The idea for the book came about when Martin decided to go on pilgrimage to the Holy Land. After initial reluctance he went with a Jesuit friend, taking a two-week trip to explore the Gospel stories in the very places where the events are believed to have taken place. The result is an extraordinary, humourous and poignant travelogue – part literature review and part meditation on the meaning of Jesus’ life. Martin weaves his story between contemporary Israel and Palestine and the Biblical past, from the concrete to the transcendent. What stays with me particularly is the description of chatty passengers on the Number 21 bus to Bethlehem juxtaposed with the meditation of the Gospel stories commemorated on that very ground.

What makes this more than just another retelling of the Jesus story is the personal connection Martin has with his subject. Jesus is the centre of the life of this man, a Jesuit priest for 25 years, and a popular Catholic writer and speaker. Although Martin would not describe himself as a theologian or a Biblical scholar, he has studied with, and knows personally, many of the best. In fact he is so well acquainted with the experts that he recounts calling one professor in California to query his conclusion that there would have been no synagogue building in Nazareth – and that meetings would have taken place outdoors.

Martin describes his own spiritual life clearly and candidly. While visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the traditional location of Jesus’ tomb, Martin experiences a vivid image of Jesus sitting up on the morning of his resurrection. The meditations that follow well illustrate the centrality of the resurrection to Martin’s perspective and ministry.

This book is an invitation to spiritual growth. Martin poses questions throughout that challenge us to mull over and pray about our faith. When he talks of the call of Peter, and other ‘call’ narratives in the Gospels, he asks us too – what keeps us from following Jesus? Here is a rich jumping-off point into deeper exploration of the Gospels, their context, and our reaction. I found myself making a list of all Martin’s references, like leads in a mystery to be followed up and mined for clues to Jesus’ identity and character.

For those who plan their own pilgrimage to the Holy Land – the Fifth Gospel, as it has been called – Jesus: A Pilgrimage will be a valuable companion. For armchair pilgrims, Martin’s reliance on Ignatian methods of using imagination in prayer bring the sights, smells, and sounds of the Holy Land to us – the heat, the strenuous walking, the colour of the water, and the sound of the lake. Christians of long standing will enjoy Martin’s insights and gentle humour, while seekers and skeptics will gain fresh insight into the Christian understanding of Jesus that may help mitigate the current cultural bias against faith. I hope that the book’s length will not deter non-believers, as it is well worth the effort. Martin’s style is clear, engaging and non-academic. As he tells us encouragingly, “You’ve met my Jesus. Now meet your own.”

A pilgrimage is both a journey outwards into the world and a going inward to what is essential. This book truly is a pilgrimage. What stays with me, having followed Martin through the journey, is a simple question he poses in Chapter 13 – what would it mean for the storms to cease and for you to live more contemplatively? What, indeed.

Hide and Seek

Ready or not, you tell me, here I come!

And so I know I’m hiding, and I know

my hiding-place is useless. You will come

and find me. You are searching high and low.

Today I’m hiding low, down here, below,

below the sunlit surface others see.

Oh find me quickly, quickly come to me.

And here you come and here I come to you.

I come to you because you come to me.

You know my hiding places. I know you,

I reach you through your hiding-places too;

feeling for the thread, but now I see –

even in darkness I can see you shine,

risen in bread, and revelling in wine.

“Hide and Seek” is from Malcolm Guite’s Sounding the Seasons, a volume of sonnets for the church year, published by Canterbury Press in 2013. His latest book, also published by Canterbury, is The Singing Bowl. Both books are widely available online, including from Signpost Music at stevebell.com/category/news.

The Stranger

A stranger passed this way and left

A stranger passed this way and left

His fingerprints on leaves of trees,

On blossoms waving bye the wind,

And petals scented on the breeze.

A spider dances to a tune,

The stranger hummed, and weaves a web,

Its fine and intricate design

An echo of that soundless tune.

I ask the plants so dewy green

To help me in my quest anon,

For footsteps that they might have seen

Or heard pass by their watchful eye.

I ask the creatures of the wood

To tell me whence the stranger came,

And voiceless voices twit and chirp

And so their bet to name a name.

I hear their plaintive, wistful sigh;

They dip their heads in soulful show;

The trees point branches at the sky,

And I glance up and want to know.

How is it that these simple folk

Have answers to my boldest dreams,

Know truths of which I have no ken,

And see the One no eyes have seen?

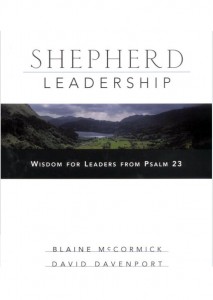

Bishop Frederick Henry: Books That Changed My Life

This is the second insta llment in our “Books That Changed My Life” series, written by leaders and innovators in our faith community.

llment in our “Books That Changed My Life” series, written by leaders and innovators in our faith community.

I now find myself moving away from the paradigm of servant leader.

The idea of combining ‘servant’ and ‘leader’ is beautiful, and extremely attractive, as we all know from Jesus’ words to his disciples in Mark 10:42-43: “You know that among the Gentiles those they call their rulers lord it over them, and their great men make their authority felt. Among you this is not to happen.” (New Jerusalem Bible)

And yet, the words ‘servant’ and ‘leader’ tend to pull in opposite directions.

An inherent tension in servant leadership can confuse our relationships with those with whom we collaborate. Servants are not usually supposed to lead, like bossy butlers.

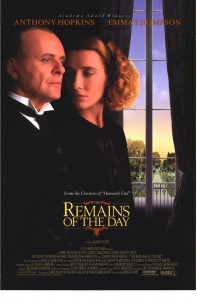

In the 1993 movie, The Remains of the Day, Anthony Hopkins portrays a most unlikely hero named Stevens, butler to Lord Darlington. As butler, Stevens manages every detail of the vast Darlington household in the late 1930s. Through a combination of hard work, long hours, quiet intelligence and denying his own needs, Stevens has become what his peers would acknowledge to be a great butler.

In the 1993 movie, The Remains of the Day, Anthony Hopkins portrays a most unlikely hero named Stevens, butler to Lord Darlington. As butler, Stevens manages every detail of the vast Darlington household in the late 1930s. Through a combination of hard work, long hours, quiet intelligence and denying his own needs, Stevens has become what his peers would acknowledge to be a great butler.

Stevens is a victim of the oppressive, demeaning class system of pre-war Britain – a social structure that permanently consigned people to roles based only on the economic circumstances of their birth. Even Stevens comes to understand how his life has been wasted living in such a system. However, despite his own foibles and frailty and that of the world in which he lives, he serves with dignity and a sense of purpose.

His fulfillment is the smooth and orderly functioning of the household and the accommodation of every member of the family, staff and guest; his satisfaction is in earning the trust and confidence of the master of the house. At the end (or the remains) of the day, we might be inclined to ask, “Is that all there is?”

A philosophy or theology of service tends to focus upon what we do rather than who we are. The latter is more important than the former, and if we know who we are, even what we do is enhanced.

We see the dramatic lesson of greatness and ‘being first’ in Jesus’ washing of the disciples’ feet at the Last Supper. He takes the place of the person at the bottom, the last place, the slave. For Peter, as for most of us, this is impossible.

However, imagine with what tenderness Jesus touches the feet of his disciples, looks into their eyes, calls each one by name and says a special word to each one. When he speaks at the meal, he speaks to them all; he does not have a personal contact with them individually. But as he kneels humbly before each one and washes their feet, he has personal contact with each one. He reveals his love to each one, which is both comforting and challenging. He sees in each one a presence of his Father. The love of Jesus reveals that we are important, that we are a presence of God and are called to stand up and do the work of God: to love others as God loves us, to serve others and to wash their feet.

By washing his disciples’ feet, Jesus does not diminish his authority. He is “Lord and Master” who wants to reveal a new way of exercising authority through humility, service and love, through a communion of hearts, in a manner that implies closeness, friendliness, openness, humility and a desire to bridge the gap that so often exists between those “in” leadership and those “under” their leadership.

What Jesus is exercising is real shepherd leadership. There is a wealth of unmined richness in this scriptural, ecclesial and liturgical metaphor, not only for clergy but also for anyone exercising leadership.

“When they had eaten, Jesus said to Simon Peter, ‘Simon, son of John, do you love me more than these others do?’ He answered, “Yes, Lord, you know I love you.” Jesus said to him, “Feed my lambs….look after my sheep…feed my sheep.’” (New Jerusalem Bible; John 21:15-17)

Two books have been very helpful to me in unpacking and applying this metaphor. The first is Shepherd Leadership: Wisdom For Leaders From Psalm 23 by Blaine McCormick and David Davenport (Jossey-Bass Publications, 2003). The second is The Way of the Shepherd: Seven Ancient Secrets to Managing Productive People by Dr. Kevin Leman and Bill Pentak (Zondervan, 2004).

Nothing New Under the Sun

(a found poem based on Biblical sayings)

If you are as old as the hills,

or as old as Methuselah

know that all things must pass

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust

But as you bite the dust

Or give up the ghost

Gird your loins and Fight the good fight

For faith will move mountains.

Set your house in order

Read the sign of the times

Follow the strait and narrow

To the ends of the earth

The writing is on the wall

To everything there is a season

You reap what you sow

From the fat of the land

So beat your swords into ploughshares

And see eye to eye

Let not the sun go down on your wrath

Make your peace offering

Love thy neighbor as thyself

And in the twinkling of an eye

Even if only by the skin of your teeth

Bear your cross

Dr. Gerry Turcotte: Books That Changed My Life

Kolbe Times is beginning a series entitled “Books That Changed My Life”, written by leaders and innovators in our faith community. This is the first article in that series.

From the earliest age I have always wanted to be a writer. I loved books, wrote books, studied books. Any kind of book. I was the type of kid who read the phone book if there wasn’t something else available, but my parents always made sure I had alternatives. Since my parents were not learned in the traditional sense, and had not come from bookish families, I was not fed on a regular diet of children’s classics. So I pretty much charted my own course, often dictated by articles about influential writers that I might find in the newspapers, and then later, at university, through the passions and prejudices of my favourite professors. I can pretty much map my reading trajectory according to the courses I took, from medieval to theatrical, Victorian to Canadian.

As a young wannabe writer in the ’80s my favourite authors were Heinrich Böll and William Faulkner, the latter of whom ruined my writing for a good 15 years as I tried to imitate his eccentric and epic style. It was not until much later that I began to return, as a writer, to what I see now as my Canadian roots, and to craft my stories through the drier, wiser tones of an Alice Munro or a Mavis Gallant, the humour of an Atwood and the poetics of an Ondaatje. I never scaled their heights, of course, but through them I learned how legitimate and exciting the Canadian view was as the subject of fiction. It may seem strange now, when a breadth of experience and subject matter is such a given, but there was a time when Canadian identity in fiction had to be argued for and championed, and where a writer like Morley Callaghan had to set his stories in Buffalo, rather than Toronto, just to get them published.

So when I was asked to write this initial column on the subject of favourite work I thought that this would be easy and my choice obvious. I considered the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s 100 Years of Solitude, or the simple complexity of Italo Calvino’s If On a Winter’s Night a Traveller. I still reel at the boldness of Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom where the story is given a heart-wrenching twist through a detail buried in the genealogy at the book’s close. I re-read Shakespeare the way one might pray the rosary, looking for inspiration, solutions to characterizations, or for the comfort of perfection.

But in the end the work that shimmers behind, around and above all others, which I turn to in depth or as a magpie seeking meaningful moments, is the Bible. Its influence on literature is impossible to capture in words. It has given us the titles to more novels than any other single work — from The Sun Also Rises to East of Eden, Song of Solomon to Leaven of Malice; more aphorisms and sayings are drawn from its pages than from any other source — an eye for an eye, by the skin of your teeth, a labour of love — with Shakespeare a distant second. And the architecture of this great and holy work teaches all writers — young and old — how to tell a story, how to move an audience, and how to make truth the centre of every tale. I am not a theologian, and you would not detect a Biblical resonance in my novels, poetry books, plays or academic writings. But the influence is there: in the texture of the writing, in the works’ moral core, and hopefully, occasionally, in a moment of inspiration that is witness to something greater than the individual voice can ever hope to become.