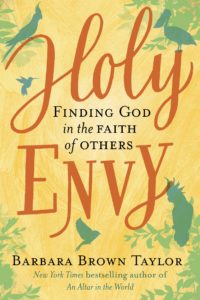

Barbara Brown Taylor is an Episcopal priest, teacher, and bestselling author of fourteen books on religion and spirituality, including Leaving Church, An Altar in the World, and Learning to Walk in the Dark, which was featured on the cover of Time Magazine, and named one of the best religion books of 2014 by Publisher’s Weekly. She has served on the faculties of Piedmont College, Columbia Theological Seminary, and Candler School of Theology at Emory University. She has been recognized by Baylor University as one of the top twelve preachers in America, and in 2015, was named Georgia Woman of the Year. Her latest book, Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others, was published in April 2019 (HarperCollins Publishers). Barbara Brown Taylor lives on a working farm in rural northeast Georgia with her husband, Ed.

It was a joy to talk with Barbara Brown Taylor about her childhood, her experiences as an Episcopal priest and a college professor, and her new book. In it she recounts, with her trademark humour and keen insight, how her years of teaching an introductory World Religions course turned out to be a life-enriching experience for both her and her students.

Here are some audio highlights from our conversation, with music by Kai Engel. (3:29)

Interview by Laura Locke

KOLBE TIMES: Welcome to Kolbe Times, and thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Thank you for inviting me.

KOLBE TIMES: Can you tell us a little bit about your childhood and teenage years? I know you didn’t grow up in a particularly religious home.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Yes, that seems to be part of the story looking backwards. You never know the shape of the narrative while it’s happening, right? But I was raised by a disaffected Roman Catholic father from Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and a pretty disinterested Methodist from College Park, Georgia. They had me baptized in the Pre-Vatican II Church to please my grandmother, and it was a horrible experience for both of them because there was much being said about their first child’s sin and wickedness. The story is my mother turned to my father afterwards and said, “We’re getting out of here, and we’re never coming back.” We never did. So I rebelled and found religion – mostly by visiting with friends, because I grew up a lot in the South, and you’re always invited to church on Sundays. So I visited synagogues and churches, Unitarian places of worship, and wandered through all of those happily for many years. I was baptized by immersion in the Baptist Church at age 16, and became a member of the Presbyterian Church during my first year in seminary, and then finally found the Episcopal Church during my final year. I was confirmed then, and several years later ordained. So it was an unexpected journey for my parents, who tried to protect me from religion.

KOLBE TIMES: Yes – I was wondering, how did your parents feel about all this?

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: They were so dear. My mother, when she heard I was going to seminary, said, “We didn’t raise you like this, and you will get over it.” But there was no hostility; there was just sort of amazement that I would be interested in something that each of them was so disinterested in. They both were confirmed in the Episcopal Church later, though I don’t think that had as much to do with God as it did with their daughter. So there was no hostility – just bafflement – of why I would choose such an odd profession.

KOLBE TIMES: My husband and I have had rather ‘interesting’ spiritual paths in our lives, as well. I grew up in the United Church here in Canada; my husband is Jewish and became a Christian just before I met him. We attended a number of Protestant churches together in our early married life, but were always drawn to the life of St. Francis. About 12 years ago we joined the Catholic Church, and also became members of the Order of Lay Franciscans. I think that’s why your recent books really appeal to me – you write so openly and eloquently about your own spiritual curiosity, and your winding path. It sounds like you were always a spiritual seeker, and continue to be.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Yes, and if you think about it, I wasn’t patterned. I mean, I wasn’t inducted into anything, because I was six weeks old when I was baptized. So I could free range because I wasn’t pointed in any direction, and I felt free to come and go. When I got in trouble with youth directors at churches, my parents didn’t care. So it really opened up the way for me to explore, really without any interference – I could say, without any guidance, I suppose – but certainly without any interference. I’m very thankful for it. And it leaves me puzzled when parents ask for advice about formation for their children, and how they should go about that. I’ve never raised children, so I have no idea.

KOLBE TIMES: And it seems like the ‘free range’ path worked out fine for you.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: I think so, too. And I’ve found that it gives me more and more to talk to millennials about. I’m really surprised by how many of them are picking up my books. And the only sense I can make of it is this: their born experience is to be seekers, because the churches that I knew when I was growing up just don’t exist in the same way anymore. So it’s a wonderful meeting ground in a way.

KOLBE TIMES: So you landed on the Episcopal Church as being a good fit for you. And during most of your time in seminary, ordination wasn’t possible for women, correct?

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: It became legal the year I graduated, in 1976. A few women, who became known as the Philadelphia Eleven, had found bishops willing to ordain them as priests in 1974. So all of that happened illegally before it became legal, and was officially authorized at the General Convention in 1976. I probably wouldn’t have been ordained without their action. But I was in no way prepared for ordination when I graduated. I had only been in a church as a confirmed member for a year at that point. So I had a lot of time to spend in a pew before I had any interest in ordination, or before there was a Bishop with any interest in me. I was ordained in 1984.

KOLBE TIMES: And then you worked as a Parish priest for a number of years.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Yes, in two very different and wonderful places. First I worked in an urban Parish, as part of a four- or five-person clergy staff, and lots and lots of lay ministry as well. I spent ten years there so happily that I could have stayed longer, but it did occur to me that I wasn’t ordained to one church in downtown Atlanta, but to the broader church. So my husband and I decided to ‘cast our nets’. We wanted to live rurally, if we could, after experiencing this really dense and rewarding urban ministry that included the AIDS crisis – more funerals than I want to count – and a lot of homelessness and upheaval in cities. So we moved to rural North Georgia. We wanted to stay in the state because our families were here. I fell in love with a little church building before I ever met anybody who worshiped inside. The rector there died on All Saints Day, and two years later – after a mandatory search period – they invited me to come. I was happy there for five and a half years, but it was a very tiny church – and it grew! That was upsetting to many of the parishioners who had loved the little church. So I left, and now it’s back to a comfortable size. I can’t believe how self-serving that sounds.

KOLBE TIMES: I imagine being a Parish priest is overwhelming at times. You’re the ‘go-to’ person when something great happens in someone’s life, and when something not-so-great happens. Can you speak about that a little?

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Well, to tell you the truth, the administration and proofreading was more overwhelming, really, than the other things I enjoyed doing. What was interesting – I think because I was the first woman rector of that church – was how everybody sort of protected me. I kind of had a ‘Virgin Mary’ position. I wanted to say, “Look, I’ve spent a lot of time in hospital Emergency Rooms, and I’ve stayed in ICU waiting rooms all night, and I’ve bailed people out of jail, and I’ve visited on death row. It’s okay.” It was an interesting mismatch between the given perspective of me and the real work of priesthood, which was much more gritty, and which I loved. And as well, I always loved the unexpected nature of Parish ministry. There was no such thing as planning my day, because the day would not conform to my plan…ever.

KOLBE TIMES: In all the experiences of Parish ministry, you would learn so much about just the human condition – as well as learning a lot about yourself.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Because I wrote a book called Leaving Church, I also learned that I wanted a ministry that had less ‘boundary’. I suppose that would make some sense given the way that I grew up. There were ways in which I loved being at the centre of an institutional form of Christianity, and one whose theology I still very much identify with – the Episcopal way. But I needed out of such respectable, predictable, and given boundaries. Working at the Parish I was in the business of forming faith, not asking questions or roaming around. So I think, in the end, it all worked out great. I ended up in a college classroom and got to ask all the questions I wanted.

KOLBE TIMES: You were invited to teach a Religions course at a nearby college. I was a teacher, too, for many years – so I know what you mean; as a teacher you have a lot of freedom. You’re kind of your own boss in the classroom.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Isn’t it wonderful? I kept looking around and saying, “Doesn’t anybody want to come check on me and see if I’m doing this right?” Because you’re correct – you can create your own little world, in a way, in the classroom and decide how you’re going to teach as well as what you’re going to teach. I loved that freedom. I definitely felt I had more freedom in the classroom than in a church. You can make a lot of comparisons between teaching a class and leading a congregation, but there was so much more pushback and argument in a congregation than what I experienced in a classroom. It might have been the age of the students, and the whole institutional setup – I’m not sure. But I’m very glad I got to do both.

KOLBE TIMES: You ended up teaching at the college level for 20 years.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Yes. Longest job I ever held.

KOLBE TIMES: And how was the transition itself, from leading a congregation to teaching in a college? Was it a difficult time for you, or did it just seem like the right thing at the right time?

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: It seemed like the only thing. I mean, my brains were on fire – and my heart was dead. So when I left this small rural church, there was a three month ‘desert’ period. I knew I had a job coming up – the teaching job – so it wasn’t an outwardly desperate time, and plenty of people go through that. So I don’t compare someone who is feeling economically terrified to the kind of vocational terror that I felt. I so expected to be a Parish Minister for the rest of my life, that even deciding what to put on in the morning was a real challenge. I had been wearing black clergy shirts to work every day, and all of a sudden, green entered my life, and purple, and blue! My closet became a lot more interesting. But I didn’t really know how to dress or talk, because Christian language was not everybody’s language anymore. So it was a wonderful way to get shaken up and face the world from a different direction.

KOLBE TIMES: Let’s talk about your latest book, Holy Envy, which is about your experiences teaching a Religions of the World course to students who were mostly 19 to 21 years old. You mention that in the U.S., southern Christians are a kind of a special group. What do you mean by that?

KOLBE TIMES: Let’s talk about your latest book, Holy Envy, which is about your experiences teaching a Religions of the World course to students who were mostly 19 to 21 years old. You mention that in the U.S., southern Christians are a kind of a special group. What do you mean by that?

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Well, you do see pockets of it all over. When I was in Arizona recently, I saw lots of Jesus billboards, which really surprised me. But in the south, that’s completely normal – so even students who didn’t identify as Christian lived in a very Christian culture. There’s no way to live in the south and walk into Walmart without knowing what Christian holiday is happening. It’s a very Christian atmosphere, all around you, all the time. My students were predominantly Christian, with some students of other religious backgrounds – mainly Muslim, a couple of Jewish students, and a few Hindu students.

There were also a lot of Seventh Day Adventists, and Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and Orthodox Christians. We’ve got a little Orthodox Church of America congregation in the next county over. So I was blown away by the Christian diversity in the area, of which I’ve been entirely unaware.

KOLBE TIMES: And fairly early in your time of teaching that course, you decided that you wanted to get your students out of the classroom and into places like Mosques and Hindu Temples and Buddhist Monasteries and Synagogues. You felt that was important for your students, and your book walks us through all these experiences.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: I think we just forget that you can’t learn about a religion in a book. You can learn dates, and geography, and you can read history, but that’s no substitute at all. I mean, one of the first episodes in that book is about going to a Hindu temple, south of Atlanta, that has been there a long time. But to walk into that place with sculpture and butter lamps and incense and motion and chanting – nothing in a book could touch that – and a video on a screen in a classroom couldn’t touch that, because there was no risk. To walk into those places introduced an element of risk that was great for the educational process, I thought. It made questions come up that would never have come up from a textbook – and I had as many questions as anyone else.

KOLBE TIMES: I love the way you talk about the importance of being on the receiving end of hospitality, instead of always being the one who invites people to your own place where you can retain some measure of control over what happens. To be in that vulnerable place of a guest, which I think you called the ‘blundering stranger’, gives you an entirely new perspective.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Definitely. To be the visitor and not the host, and to make mistakes and to be forgiven and welcomed and fed and given gifts – all that can really increase your humility about your own tradition, and also might lead you to think about how well your own tradition does the job of welcoming strangers. There was a lot of reflection on my part, and that of the students as well, about how we were being received with such kindness as guests, and to wonder whether our own places of worship and study were similarly hospitable to people of other faiths. I think that was not just my experience, but the students as well, because we were treated unequivocally with graciousness.

KOLBE TIMES: My husband and I took part in a local interfaith program called “Meet Your Muslim Neighbour”. We were invited to have supper in this lovely Muslim family’s home, and since then we have become friends. On that first evening, we asked them all kinds of questions about their faith and their traditions, like Ramadan, and their five daily prayers, and their various festivities throughout the year – and they were very open and gracious and I would say even quite excited to answer our questions. We learned so much! And then they started asking us questions about our Christian traditions, like Advent and Lent – and we also talked about Mary’s role in both our faith traditions because, as I discovered, she is venerated as one of the most righteous women in Islam. I found that whole dialogue so refreshing – asking questions so openly and answering their questions. And another great thing is that answering their questions reminded me of the beauty and significance in some of our Christian beliefs and practices. It was all kind of amazing.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Oh, I love that. And that’s why I called the book Holy Envy. Whether or not you identify with the ‘envy’ part, there’s a holiness to it, when you get to that level of answering questions and being asked questions – questions that other Christians are never going to ask you. And the Mary connection is wonderful; to find out that some of our Christian traditions and characters show up in other traditions as well.

KOLBE TIMES: Another thing I’m grateful for is my husband’s Jewish background. We celebrate many of the Jewish holidays. At first, when our kids were small, we tried to add a bit of a “Christian spin” on celebrations like Passover and Hannukkah, but we soon changed our minds and decided not to add that anymore.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: You’re doing, ideally, what I taught – which is that you don’t need to muddle the traditions. They can stand side-by-side and enrich each other. So I love what you just said.

KOLBE TIMES: I really enjoyed reading in your book about the epiphanies that you and your students experienced as you visited all these different places of worship, and how so many stereotypes and assumptions were turned upside down. I also want to mention that your book has a lot of humour in it as well. I found myself laughing a lot as I read it, and I could really identify with many of the things that you and your students felt. It must have been quite exciting for you, during all those years of teaching this course, to witness the discoveries your students were making.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Sacred – really, truly sacred; it was just a wonderful thing. I never got bored. And I never taught the class the same way twice, because the students were never the same way twice. It was endlessly refreshing.

KOLBE TIMES: And that reminds me – you talk about how teaching this course to these students felt almost like a sacred responsibility. You wrote that you wanted to “give their imaginations something better to work with than what they were getting from the movies and the news”, and to help them find the bridges between faith traditions. With our communities becoming so increasingly pluralistic, I can really see the huge importance of that.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: I don’t think many Christians think about what it would be like to live in another country and take a world religions class taught by say, a Muslim, or a Buddhist or a Hindu or a Jew – and to hear them approaching your tradition, and just hoping so much that it will be presented fairly and at its best. So to be given that responsibility myself was huge, and I had to keep remembering how ‘on edge’ I would be to receive information about my tradition from someone else. And I wanted that person to be a person of good faith…so I tried hard to be one myself.

KOLBE TIMES: What do you say to people who might ask you about the danger of somehow watering down our Christian faith when we explore other religions or incorporate some of their wisdom or practices into our lives?

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: I think the experience itself can teach us about that. Was your faith watered down when you let Hanukkah be Hanukkah? Was your faith watered down when a Muslim family asked you about Lent, and when you asked them about Ramadan?

KOLBE TIMES: No, it sure wasn’t. If anything, it deepened my faith, and made me think about it more seriously.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Sometimes I think that if Jesus could hear us talking about loving our neighbors as watering down our faith, he would have a belly laugh! I mean, I do think there are dangers. I think regarding holy envy, if you take the ‘holy’ away, you might try to assimilate and poach and borrow things from other traditions that are not yours, and spin them in a way that would be abhorrent to the person you borrowed it from. And I think there could be spiritual dangers as well, especially if someone becomes interested in the darker arts like Wicca, or in different forms of spiritualism. You can wander into some pretty deep spiritual territory, and you want to be sure you have a light or a companion or a map or something. So, yes, there could be dangers – because when you think about it, show me a ‘safe religion’. I’ve never heard of one yet. But when I ask myself about the students that I’ve known, were they harmed by losing their stereotypes about other faiths, or by making friends of people from other faiths by entering into community with them? There’s no evidence in two decades. And there’s no evidence in my own life, either.

KOLBE TIMES: You also point out in your book that in the Bible, we often see Jesus engaging with people from other faith traditions, and we don’t see him condemning them or being wary of them. That gives me a sense that there’s actually a strong invitation, especially in the New Testament, to be more open to the ‘other’ – and that there is a great benefit for us when we accept that invitation.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: It was interesting that the first time I taught this course, and came to teach the unit on Christianity, I tried to find the central beliefs and practices of the Christian faith. So the first thing I tried was the Nicene Creed – and that didn’t go very far. The second one I tried was the Sermon on the Mount, and that went very far. So how do we see the centre of Jesus’ teachings? Is it the religion of Jesus, which I believe is available in the Sermon on the Mountain in Matthew, or the Sermon on the Plain in Luke? Or do we locate it in the Nicene Creed? Many Christians locate it in John 14:6 – “No one comes to the Father but by me.” I think we’re all called to say something about how we reach our decision about Jesus’ central teachings, because how else can we measure our faithfulness to them? So you can hear that I’ve staked my lot on the Sermon on the Mount, which is all about giving yourself away for the other, as far as I can tell. It is a radical egolessness that is called for in that sermon, whether it’s praying for enemies, or giving to everyone who asks of you, or loving the neighbor as the self. Jesus is meaner to the Pharisees – to his own group – than he is to anyone else in the New Testament.

KOLBE TIMES: When I listen to you give talks in videos, and when I read your books, you always make me want to read the Bible more. You seem to delight in showing us Bible stories from new angles, and you always bring fresh insights along the way. I also love how you often point out Bible verses that we don’t hear about or think about very often. I sense you have a real love for Scripture.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Yes, I do. I wish as many students had taken the Introduction to the Bible course as took Introduction to World Religions – just because we’re all called to take some responsibility for how we read and why we read and why we privilege the parts we do and why we ignore the parts we do. And that’s refreshing. It’s almost like being asked to explain Advent or Lent, right? Why do I read Scripture the way I do? Why do I think what’s true is true? It can get heated, as you know. Sometimes defenses can go up pretty quickly. I just keep taking a deep breath.

KOLBE TIMES: I appreciate the way you model how we can grant ourselves the freedom to dare to look at things from different perspectives. I sense that, by your example, you gave your students that freedom as well.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: And with my students who were Christian, I would use the language of the Holy Spirit sometimes – that the Spirit, in our Christian teaching, is within, and it’s a guide. It’s been given to us by the other two members of the Trinity. I would tell them that they could trust the Spirit within them when they walked into these strange places. I think that’s a Christian teaching. I didn’t have to leave my tradition to say to them, “You have wisdom within you, so use your wisdom. And if your wisdom tells you to go outside and wait in the school van until we’re finished, please know that you will get an A+ for coming on this trip, and there will be no penalty for sitting out parts of it.” So whichever way their wisdom led them, that that seemed a good way to go.

KOLBE TIMES: You also point out that as Christians many of us have lost this desire and this ability to hash out and discuss and argue and think deeply about the Scriptures in that kind of Jewish “Midrash” way. When I read your books, I always have my Bible close by, because your writing encourages me to look again at Scripture in a way that maybe I haven’t before. I think that’s what we need, so that we can navigate the world today – to stand up for what we think, and also to listen to other points of view and other ways of looking at things, even in our own religious tradition.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: I love your reference to that impassioned Jewish discussion about the meaning not only of Torah but Talmud; it’s about loving the text. That kind of sacred dialogue can get very heated, but it’s a heat that takes you deeper into the revelation. That’s my ‘holy envy’ of Judaism. But I know that I have a tendency to idealize other religious traditions. It’s been fun to get letters and ‘loving critiques’ from people in other faith traditions about my tendency to do that, and reminding me that we’re all just people – and wherever there are people, we can be both saints and sinners.

KOLBE TIMES: So at the end of the day, what is it about your Christian faith that still really speaks to you?

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: Jesus’ central teachings, among which I would include the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew, and the Sermon on the Plain in Luke. I would include Jesus’ reply when someone asked him what the greatest commandment is, and he said, “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment; and the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’.” I would also include the Lord’s Prayer. There’s no self reference in any of those; there is instead a focus on the transcendent and immanent God. So those central teachings, and also my love of exploring Scripture, keep me Christian.

Someone once said that Christianity is the way that is open to all other ways. Even if that’s got a little hint of arrogance in it, I love that idea – that through those central teachings, I belong to a way that is meant to be open to all other ways. So I can visit a Shabbat table, and be blessed by that. I can stand at the side of a room where a crowd of Muslims are praying for God’s will to be done in their lives, and be blessed by that. That just seems to me something that comes with my Christian heritage.

I’m not leaving my own tradition to be blessed by those other ways that God comes to people. And by the way, Catholic theology has been brilliant in that area. We won’t start that whole other conversation, but suffice to say that most of the people who have meant a lot to me, in making Christian sense of religious pluralism, have been Catholic.

KOLBE TIMES: Thank you for talking with us today. It’s been lovely.

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR: You’re so welcome. I’ve really enjoyed talking to you, too. And I’m grateful for your good work through Kolbe Times.

Visit www.barbarabrowntaylor.com

Photos courtesy of Barbara Brown Taylor.

Different questions and answers and sentences in this article shine just a little more light in to the nooks and cranies and cracks and blind spots in my mind and in my consideration of religion. Thanks for that.

I felt the same, Charlie. Talking with Barbara, and reading her books, has given me such fruitful and interesting food-for-thought.

Reaching out to people of different faiths, listening to them and praying with them has been most invigorating. They

have brought new life and enthusiasm into mine.