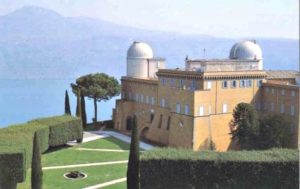

Br. Guy Consolmagno SJ is a Jesuit brother who is currently the Director of The Vatican Observatory in the town of Castel Gandolfo, 25 km southeast of Rome, Italy. The Vatican Observatory is one of the oldest astronomical institutes in the world. In 1980, a new division of the Observatory was established on Mt. Graham in Arizona. Br. Guy is also President of The Vatican Observatory Foundation, which exists to support scientific research into knowledge of the universe, and public education based on that research.

Br. Guy was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1952. He earned a Ph.D. in Planetary Science from the University of Arizona in 1978, and took vows as a Jesuit brother in 1991. He also studied philosophy and theology at Loyola University Chicago, and physics at the University of Chicago before his assignment to the Vatican Observatory in 1993. Br. Guy was honoured in 2000 by the International Astronomical Union for his contributions to the study of meteorites and asteroids with the naming of “Asteroid 4597 Consolmagno”, and in 2014 was awarded the Carl Sagan Medal for Outstanding Communication by a Planetary Scientist by the American Astronomical Society. He is the author or co-author of six books, two on astronomy and four exploring religion and science. Our conversation with Br. Guy was filled with light and laughter, as we learned more about his life, his faith and his love for astronomy.

Here are some video highlights of our interview:

Interview by Bill Locke

Kolbe Times: Thank you so much for joining us today, Brother Guy … I really, really appreciate your opening up to me this morning, especially when it’s your first cup of coffee!

Br. Guy Consolmagno: (Laughs) It is.

Kolbe Times: I know you’ve told this a million times before, but I would like to hear it…and that is, your journey leading up to your current position as “the Pope’s Astronomer”.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: Oh, it’s a fun story. The important thing, I think, is to put it into its context. I’m a “baby-boom kid”. So I grew up after the war, and in the 50s, this was a time of tremendous optimism, a tremendous faith in science – you know, science won the war … and science had just cured polio … and science was going to solve our problems. But at the same time, it was also a very strong moment for the Church. The Catholic schools were booming. I think a lot of soldiers coming back from the war recognized the need for a spiritual side to their lives. And so, when I was in grade school, I learned science from the nuns. And I’m not talking about, you know, “bad” science. I’m talking cutting edge science; really good science. The Sisters that I had in my grade school in suburban Detroit were phenomenally good. They were tremendous teachers; they were tremendous people; they were great examples to me – and they really encouraged me in my science. I was also a boy at a time when all boys were going to be you, know, scientists or engineers. Girls, not so much. This was the 60s.

And being the son of, you know, an Irish and an Italian, I had the Catholic in me, in my blood … both of them college-educated, and in both cases not even the first of their generation to go to college. My Italian grandfather was a lawyer. So, there was a lot of education in the house, and there was a lot of reading in the house. But there was also a Catholicism that was not extreme, or ‘in your face’, or far left, or far right, but just an unspoken core that was a tremendous gift.

I think of all the gifts that I got from my parents – and I think tremendous gifts; they were the most incredibly wonderful people – but they gave me this self-confidence to feel at home in the world, not afraid to try out new things, not afraid to explore, and not afraid to say, “I don’t know. Let’s find out.” And that turns out to be key, both in a life of science and a life of religion, because in either one, if you think you’ve ‘got it’ ahead of time, then you’re dead. Then it’s frozen, and it withers.

As a little kid, of course, I was asking, “What do I want to be?” My father was a journalist. My grandfather was a lawyer. I liked writing. I liked talking. I also liked the priests at my parish, where I was the altar boy. I liked all of these things.

They had a science program for fourth graders at my school, which I took part in. It was held at the Jesuit High School, and so that’s how I met the Jesuits. Later, when I went to high school there, everyone said, “All the top kids do Latin and Greek. The second-best kids do Science. And don’t worry about not doing Science, because you can always get that in college.” They were right, actually. So I did classics – I did Latin and Greek in high school, and I thought I’d go into journalism or history. I actually even got a summer job at a little paper in Michigan as a journalist. I discovered how to write quickly and, being a reporter, I learned a lot about how the world works. I also discovered I was terrible at it. And what I was terrible at was calling up total strangers and asking them embarrassing questions – which is something you’ve got to be able to do if you’re a journalist.

Meanwhile, not knowing any better, I went to Boston College because I wanted to go to school in Boston. That was my where my dad was from. And I wanted to go to a Jesuit school, in case I decided to became a Jesuit. This was 1970, a time when the world was crazy there. There were demonstrations against the (Vietnam) war, with student strikes and all sorts of things. I didn’t fit in at Boston College – it seemed all the other kids in the dorm basically just wanted to drink, and I wanted to study. And of course, after they would drink too much, then they would come and pour out their problems to me, and all I could think about was “Why are you telling me all this? You’re the idiot. Leave me alone.”

Since I didn’t fit in, I figured, well, maybe I should be a priest. A girl I dated in high school had dumped me, so I figured there was no future there, foolishly. I went to a priest, who said, “Well, have you prayed about this vocation?” I thought, “I’m 18 years old – who prays? Give me a break.” But I went back to my room, and I sat on the floor, and looked at the ceiling. I asked for a voice in the ceiling to tell me what to do.

Nothing happened, and while I was sitting there feeling really foolish, a thought popped into my head: “If I become a priest, what would I be doing? I’d be working with people. Just like the people that I didn’t want to call up for the newspaper. Just like the people pouring out their problems to me in the dorm, that I don’t have any patience for. Boy, that would be a terrible job. Oh – God is answering my prayer and telling me not to be a priest!”

And of course, you really know it’s the voice of God when it’s the last thing in the world you expect…but it sounds absolutely right.

So then I started thinking, “Well, if not that, then what should I be doing?” My best friend from high school was going to MIT at the time, which is just down the road from Boston College. I used to spend all my weekends hanging out with him, because it was much more fun there. I thought, “Why don’t I transfer there?”

Now I didn’t have the background; you know, I was a ‘classics’ person. But all the doors fell open. When I went for an interview at MIT, I said I was thinking of being a science journalist. The rest of the interview was the interviewer trying to convince me to come there. And they let me in! For the first time, I felt like I was someplace where I belonged. I absolutely loved what I was doing. I went through, got a Bachelor’s and a Master’s. My Bachelor’s thesis was good enough that they told me to keep working at it and we’ll turn it into a Master’s thesis. It was wonderful to work on, exploring the evolution of icy moons. It’s still relevant, even though it’s about 45 years old now. The ideas are still current, which is not because I was bright, but because my advisor who gave me the topic was very bright.

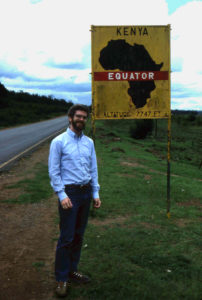

Then I went to Arizona and did my doctoral work there in Planetary Science, and had a really rising career until I hit the age of 30. And at that point, the doors were not being opened. I couldn’t figure out why, but there was something wrong, something missing. I did two crazy things when I turned 31 – one was to start dating an undergraduate, who was a wonderful person, and she was also quite a bit younger than me. And the other thing I did, in order to change my life, was to join the Peace Corps. I left for Kenya, and this girl I was dating and I corresponded all during that time. But it gave me time to reset, to think about who I was, and what did I really want to do with my life. Am I going to leave science? Why am I doing Astronomy? Why keep writing papers, when there are people who are starving in the world? That ‘Jesuit conscience’ never left me.

As soon as I got to Kenya, I found out that they had discovered I had a doctorate in Astronomy, and so they assigned me to teach Astronomy at the University of Nairobi. And that’s where I learned why we do astronomy, and why it’s important. I would go up-country every weekend to my other friends that were in the “real” Peace Corps, and I would take my little telescope, and a few slides to give a talk about the latest news from space. And everybody wanted to look through the telescope, and everybody wanted to know about the moon and Jupiter and all those places we had been studying. Of course they did – because this is what makes us human. This is what makes us more than just well-fed cows.

Many years later I reflected on the message of Genesis. The seven days of creation, among other things, shows that God made the universe and made it in an orderly way, and saw that every step was beautiful. But the ultimate point of Genesis is the seventh day, the Sabbath. And what is the Sabbath? It’s the time when we don’t worry about filling our stomachs … and instead, we fill our souls. And that is why we were created to be astronomers, or artists, or people of prayer, whatever it is we do that fills our souls.

And if you deny that to somebody just because they were born in the wrong continent, or the wrong time, or the wrong gender, or whatever excuse you want, is to deny them that humanity.

I came back from the Peace Corps filled with this enormous enthusiasm for astronomy that I had lost when I was just doing it to make a living; when I was trying to get the bigger grant and the better job. And that’s also when I and the girl I was dating realized that we were not right for each other…which was a great relief for both of us. She’s gone on to have a wonderful life, and I wound up being a professor at a little college in Pennsylvania, and that was wonderful, too. But there was still something missing – something that I had in the Peace Corps. It was about not just doing this for my own career, but for a bigger purpose, with a bigger sense of why I was doing it.

The M65 Galaxy, an intermediate spiral galaxy about 35 million light years from earth, in the constellation Leo.

A couple I knew from the Peace Corps were getting married, and I was at their wedding, very happy for them. But during that weekend I figured it was time to pray again. I went to the room where I was staying, closed the door, looked at the ceiling, and said, “Now what?” And that’s when the second surprise – an answer to a prayer that I didn’t expect – happened. I knew already that I wasn’t cut out to be a priest, but the message this time was, “You could be a Brother.”

My response was, “What?” People tend to think that Brothers were the people who did the cooking and drove the school bus. But no – a long time ago I had met a Jesuit Brother with a doctorate, and this was the first I had thought of him in 20 years. Maybe this was something I could do. So many of my friends, including the women that I’d dated, had been telling me for years that I should be a Jesuit. Now it seemed like maybe they were on to something. They knew me!

So I entered the formation process, and it was like that moment when I started attending MIT – suddenly I was where I belonged. I assumed that eventually I would be teaching at a small Jesuit college somewhere. Instead, after my training, after my novitiate, and after a couple of years in studies, a letter arrived from Rome announcing that I was being appointed to the Vatican Observatory. They didn’t ask me; they told me. It was that Vow of Obedience. You know, of the three Vows, that’s the hardest to get used to. Poverty and chastity I’d been used to – I’d been a grad student – but I always had trouble with obedience!

So they sent me to Rome, and it’s the only appointment I’ve ever had as a Jesuit. I was there as an astronomer for 20 years. And then, when I was in my early 60s, they were going to appoint a new Director of the Observatory. I knew who they were going to appoint. It wasn’t me.

But I was wrong.

Again, without asking for it or expecting it, I was told that I was the new Director! And so, for the last five years, that’s what I’ve been doing. And while all this was never my choice, it has been a tremendous joy. Even in the times when it was tough – and there have been tough times, believe me – it was great to be able to do it for someone I loved, which in this case is the Lord. As I hear from all my married friends, I think that’s true of a good marriage too. When things are going great, it’s great. And when it’s tough, you also love to keep at it, because you want to show your love during those times, too. So anyways, that’s how I wound up being the Director of the Vatican Observatory.

Kolbe Times: Fascinating. It’s so great to hear about your journey, with all the twists and turns. It reminds me a little of our own journey with Kolbe Times. It was something we kept being drawn to, and couldn’t seem to get away from. And yes, it’s been very challenging in some ways, but we love it…and it’s given us the opportunity to talk to and meet people from around the world that we would never have met otherwise – like you – and share all this with our readers. So it’s been a tremendous blessing.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: And that reminds me how, as the Director of the Observatory, I’ve had the chance to travel to every continent – even Antarctica, where I spent six weeks collecting meteorites – and to meet people all around the world.

Kolbe Times: You know, I also couldn’t help thinking, as you were talking about those times when you heard the voice of God in answer to your prayers, about the idea of having a “religious experience”. There’s something ineffable, and yet very real, when we have an encounter of that sort. It made me think of Thomas Merton, who writes about having that kind of experience on the corner of 4th and Walnut.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: Yes! There is a plaque at that corner in Louisville, Kentucky, which says that this is the corner where Thomas Merton had this enlightenment, this revelation – which I think is just wonderful.

Kolbe Times: He had this incredible experience of seeing all these people and realizing that he loved them, and that we all have this deep connection. This very articulate writer had a hard time describing what had happened, and yet it opened up a new realm for him.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: This is key to the discussion of science and religion. I say that because people who have not experienced or recognized those religious experiences, and people who haven’t actually ‘done’ much science, too often have this mistaken idea that science is all rational and based on data, and religion is all fuzzy. But in reality they are much more the same than they are different. Here’s what I mean: every religious experience starts with … an experience! It starts with a moment when something happens. And just because I can’t articulate it doesn’t mean it wasn’t real, and I might spend the rest of my life trying to articulate it…and that’s what turns into poetry…and that’s what turns into religion. Trying to explain a religious experience to someone can feel like trying to explain married love to a seven year old. They’re just not prepared enough to understand what you’re talking about. They don’t have anything in their own life experience that they can relate it to. Now, in the same way, with science you start with the data but then there is this intuition, that comes from who knows where. That intuition might make you say to yourself, “I’ll bet if we do this, then maybe we’ll get that…though maybe it’ll be a little different.” Without that intuition, you can’t do science, no matter how bright you are. I was in grad school with this fellow who was the smartest student – on paper – that you would ever meet. The New York State has a statewide High School Regents Exam. He came in number one in his year. He was not only really smart, he was hard working, too…but he didn’t have that spark of imagination, that weird spark that allowed him to do the science. He could do whatever you told him to do, but he couldn’t see for himself what to do next. He was smart enough to know that science is not what he was cut out for, and he’s gone into another field where he’s done extremely well.

Religion and science really share this talent of, on the one hand, being open to the intuition, to being open to recognizing the experience – and then being able to think logically about it. There’s a famous line that Isaac Asimov, the great science writer and science fiction writer had. He said, “The most exciting thing you hear in the lab is not, “Eureka, I’ve discovered it!” It’s when the scientist goes, “Huh, that’s funny.” And what is not said then is you have to be open to recognize that something’s ‘funny’, rather than only seeing what you expect to see. And that’s true in the life of religion, and that’s true in the life of science. They’re so close together; they both take the same talents.

Kolbe Times: Do you remember the story of the German chemist Kekulé’s great breakthrough, when he had a dream about the molecular structure of Benzene, C6 H6? One of the great discoveries in chemistry was from a lucid dream.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: Yes. People sometimes asked me how many hours a day did you work on your Ph.D. thesis, and the answer was twenty four. Your brain is thinking even when you’re dreaming, even when you’re riding the bus, even when you’re taking a shower. Some of your best ideas come when you’ve stopped trying to think about it, and your mind is free to make new connections. I think it’s similar to why you sometimes hear it said that a person with a neat desk will never be a good scientist. You need to have different pieces of paper sitting randomly in front of you so you can say, “Oh, wait a minute – that’s the same as that! They belong together!”

Kolbe Times: So what would it be like if scientists were to apply the principles that you’re talking about, which would include embracing the kind of methodology, the kind of heart, that accompanies religion at its best.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: Oh, but they do! And that’s the other unspoken connection.

There’s a bumper sticker that I’ve seen, which makes me chuckle – it says “I love God. It’s His fan club I could do without.” So many folks these days are turned off by the very ‘churchy’ kind of religious people who don’t really get what God is about. And the same is true of science. I love science, but it’s the fan club that drives me nuts. The people who think science is totally cut and dried and gives us these eternal truths are not scientists. People who believe in “scientism” – this excessive belief that science is the only reliable source of knowledge – are trying to turn science into a religion. The last thing in the world that a scientist would want is for that to happen.

I’ve found that most scientists, certainly of this current generation who are my age and younger, are very open to religion. A lot of them practice their faith. And if they don’t, it’s often not because they don’t believe in God, but because they didn’t have the good examples of the nuns that I had in my early school years, who refused to simply tell their students that “all the answers are in this Book.” And I know people who have been turned off science in exactly the same way, because they didn’t have good science teachers.

Kolbe Times: I’ve heard you speak about the fact that there is an important place for doubt in our lives.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: Yes. That might have been when I was quoting something from a book by Anne Lamott…but it turns out the quote actually goes back to Paul Tillich. Anne Lamott is a wonderful popularizer of religion, and Paul Tillich is a very serious theologian. And she says in one sentence what he takes about 20 pages to say, though far more eloquently – and her line is “the opposite of faith isn’t doubt – the opposite of faith is certainty.” You know, if you’re certain about something, you wouldn’t need faith. And indeed, it would cancel faith. But we’re never certain about things. We ask ourselves, you know, did I choose the right school? Did I choose the right career? Am I dating the right person; am I living in the right house in the right town? There’s no way you can know ahead of time…and sometimes you get it wrong. And yet you have to make these decisions in the absence of knowing for sure. Therefore you have to go on faith.

Do you remember the movie, oh about 25 years ago, called ‘Jerry Maguire’? There’s a little kid in the movie who is very precocious; he’s about five or six years old. In the middle of any conversation he’ll tell you all these facts, like how much the human brain weighs. That’s a little kid’s idea of science. “There are nine planets in our solar system, and I learned that from my book, and therefore there will always be nine planets.” And if you try to tell him about Pluto actually not being considered a planet, he’s just going to refuse to listen “because I learned that there are nine planets from a book, and it’s a fact.”

Well, science is about trying to understand what makes something a planet, and what makes it different from something else. And you discover, “Oh, it’s not as easy as we thought!” But if you aren’t given the chance to get beyond the stage of the little boy in the movie; if you stop learning at a young age, then it becomes all about ego. And I’m sorry to say that too many of our public faces on television, either in science or religion, are still selling this. You know, the preacher who’s not actually there to save your soul, but wants you to believe that he’s holy. He cares more about what you think of him than what God thinks of him. And the scientist who is in love with the idea of making you think he’s the next Isaac Newton, rather than saying, “I don’t know the answer. Let’s find out.”

This takes me back to that gift my parents gave me, of having the self-confidence to not worry about my ego; the self-confidence to understand that I’m not in it to show the world how smart I am. Trust me, in everything that I can do, I know someone else who can do it better than me. I’ve met a lot of really smart people – I’ve hung out with them all my life. And I also know that there’s no way I can somehow gain points by trying to appear “holier than thou”. I’ve know some holy people, trust me, who are very close to God.

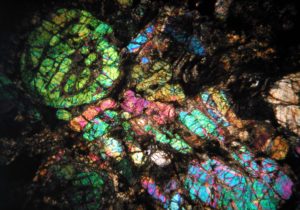

A thin section of the Knyahinya Meteorite, imaged through polarized light by Br. Guy at the meteorite laboratory in the Vatican Observatory.

So why do I do the religion? Why do I do the science? If it’s not to get people impressed with me; if it’s not to make money? It’s not to get girls, you know, obviously, it didn’t work with me. Then why do I do it? I do it out of a joy that happens when I’m close to truth. Because when I’m close to truth is when I’m close to God. And God is the source of all joy. Which is a very elegant way of saying I’m doing it for the fun of it because, by golly, it’s fun.

Kolbe Times: So how does science bring out mystery?

Br. Guy Consolmagno: Oh, you wouldn’t recognize there was a mystery if you didn’t know what was normal. You wouldn’t know what was “unnormal”. You wouldn’t know when to say, “Huh, that’s funny.” I think we’re closer to the truth than we were 1000 years ago, but what’s more important is that we’ve got new and interesting questions that they wouldn’t have thought to ask 1000 years ago. And it hasn’t finished. You know, the year 2020, thank God, is not the apex of human understanding and human society. There will be a year 2030, whether or not any of us are around to see it. And that is a profoundly religious statement. Because it’s not that the religion tells me this bit of science works, but the religion underpins; it is the source of the assumptions I make about what I expect to see in the universe. And the fascinating thing is that the great religions – Christianity, absolutely, and Islam and Judaism, and Hinduism and Buddhism – have all survived changes in the way we understand the universe, changes in our scientific understanding of what goes on, because they are tapping into something that is true, that is not dependent on how many planets we think there are. And anybody who doesn’t recognize that is missing something fundamental about what’s going on in these religions.

You know, in all of the horror of 2020, I also see a tremendous hope. I see people motivated in a way that they weren’t motivated a few years ago. I see people aware of the problems and the urgency in a way that they weren’t a few years ago.

And people have realized that they’re not going to solve the problems on their own. People are realizing, “I’m going to need not only the people who I have found as my friends and neighbors, but even the people who I think of as those idiots who are voting for the other side. I need them. I need their skills, I need their passion. I need to hear about the things that they’re afraid of, so I can respond to that as well.

Kolbe Times: There’s a lot of truth to that. We need each other, perhaps now more than ever. So, what’s next for Brother Guy? Have you got any plans? Are you hearing anything from the ceiling?

Br. Guy Consolmagno: Well, normally I would be in Rome this time of year, but because of the COVID virus, I’m still here in Tucson, Arizona at our second research center, on Mt. Graham.

The Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope (VATT) on Mt. Graham, Arizona – sometimes called “The Pope Scope”

I wear two hats: I run the Vatican Observatory, which means basically that I make sure the people in the observatory have the things they need to be able to do the science – and then I try to get out of their way. Fortunately, there is a great staff in Rome, who have been able to handle things while I have not been there, and they email me for anything I need to do.

The other thing is this: the Vatican Observatory has been around for 125 years, so that the church can show the world that it supports science, and that’s something we still need to do today. I think most scientists get it now. Maybe a number of church people don’t.

But in order to show the world and do the science, we’ve set up a foundation here in the United States called The Vatican Observatory Foundation. So with my other hat, I’ve been working a lot on expanding the work of the Foundation. Part of that is fundraising, of course, but it’s also to help more people know that we exist, and to have a bigger web presence. Every day somebody writes an article about science on our website – sometimes with a religious kick, and sometimes just because, “oh my gosh, this is glorious and beautiful” – which to me is also a religious kick because glory and beauty come from the Creator. We get 500 to 1000 people reading that every day. I want to have ten times as many people know about the website, to enjoy the great things that these people are writing.

I also want to be able to set up workshops where we can have teachers come and immerse themselves in astronomy. We’ve done that a few times now, having teachers come here to Tucson, and we were supposed to do it this year again, but the virus has caused us to postpone it. I want people to have the same experience that my friends in Kenya had, when I set up the telescope and everybody got a chance to look through it and they saw the rings of Saturn and said, “Wow!” I want to be able to share the science we are doing with the telescope that we’ve built here in southern Arizona, which is why I’m here half the year. I want to be able to share that science, and what’s more, to share the fun – because it is in that joy that we encounter God.

I can think of terrible moments in my life when things have gone very wrong, and I was able to go outside and look at the stars, and know that they’re going to be rising again tomorrow night, and that there is something bigger than me and my immediate woes. There is beauty and joy.

I was in Rome during 9-11 and experienced the terrible shock that was felt by everyone in the world. Certainly the people in Rome felt it. There was a time of great gloom, but our Observatory is on the lip of a volcanic crater with a lake – a beautiful setting. There are winds that come up the side of the crater and people like to hang glide there. And you know, in the midst of this gloom, seeing a bunch of strangers hang-gliding in the winds gave me so much optimism. There is still joy and beauty, and by golly, we human beings can invent ways to do something this cool – though you would never catch me going up on one of those things myself because I’m terrified of heights – but I’m so delighted that people can do this.

The Horsehead Nebula, a cloud of dust and gas in the constellation Orion, about 1500 light years from earth.

And I hope that the astronomy that we do is kind of like hang gliding, for people who wouldn’t want to necessarily spend their lives doing the astronomy, but who certainly can enjoy watching, and cheering us on, and laughing when we get it wrong, and smiling when suddenly we get an insight. So that’s what I’m hoping to do for the next five years or so. I’m not planning to spend more than 10 years in this job as Director, which I’ve had for five years so far. I look forward to someday maybe retiring, maybe going to teach at a small college, like I always wanted to – though I have a feeling the technology of teaching is very different from what it was like when I was a student. But that will be exciting to learn about.

Kolbe Times: I think you’ll probably have fun wherever you are.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: That’s the goal. If you find God, then you’re going to find fun. And astronomy is one of those things that cuts across politics, across race, across regions, and across religions. We all live under the same sky.

Kolbe Times: That’s beautiful – and I think it’s vital that we share the wonder that drives us, which seems to be your mission. Then the wings of faith and reason will continue to fly.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: And of course, what you’re doing with this interview is key to my mission, so I’m very grateful.

Kolbe Times: It’s been our pleasure, believe me. I’ve really enjoyed our time together today.

Br. Guy Consolmagno: God bless you, and thank you for everything you’re doing at Kolbe Times.

All images courtesy of Br. Guy Consolmagno

For great astronomy resources and and news, visit the websites of The Vatican Observatory and The Vatican Observatory Foundation

Loved this interview, where do you find these people? It speaks to my own journey in life.

I look forward to the Kolbe Times and savour every article reading only one at a time.

I found this interview very enriching: Brother Guy’s journey, the connection he makes between religion and science, and the necessity for intuition in both along with the importance of doubt. One hears the truth of lived experiences in his words.