Dr. James Finley is a member of the Center for Action and Contemplation’s Core Faculty, along with Fr. Richard Rohr and Cynthia Bourgeault. He is also a contemplative teacher, author and retired clinical psychologist. James leads retreats throughout the United States and Canada, attracting men and women from all religious traditions who seek to live a more contemplative way of living. Early in his life, James lived for six years as a cloistered monk at the Trappist monastery of the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, where the well-known monk and author, Thomas Merton, was his spiritual director. James currently lives with his wife in Santa Monica, California. It’s been 40 years since his book Merton’s Palace of Nowhere, considered by many as the standard text for exploring and understanding Merton’s thought, was first published. A special 40th anniversary edition was published this year.

James Finley. Image credit CAC staff, copyright 2018 by CAC. Used by permission of CAC. All rights reserved worldwide.

Alana Levandoski is a song and chant writer and recording artist, in the Christian tradition, who lives with her family on an aspiring permaculture farm near Riding Mountain National Park on the Canadian prairies. Her recent albums include Behold, I Make All things New and Sanctuary: Exploring the Healing Path (which was her first project with James Finley). This fall she is recording a new children’s album of songs and meditations inspired by Irish author Noel Keating’s recent book Mediation with Children, based on his work in bringing meditation to schools across Ireland.

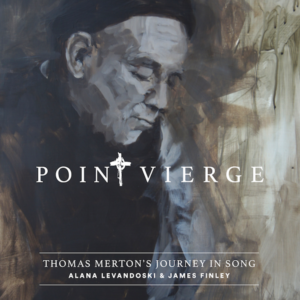

We recently interviewed James Finley and Alana Levandoski about their latest album project, Point Vierge: Thomas Merton’s Journey in Song.

Three short clips to enjoy from the Point Vierge album:

The General Dance:

What We Are:

Palace of Nowhere:

Kolbe Times: Alana, can you tell us a little of the “back story” – how you first came to know James, and how the idea of doing this album together about the life of Thomas Merton came about?

Alana Levandoski: It was the winter of 2012 and into 2013. I was purchasing a bunch of books that were recommended reading for the Living School at the Centre for Action and Contemplation. That was the inaugural class, and I had heard of James before, but I had never read his books. One of his books that I ordered was Merton’s Palace of Nowhere. I had already had a kind of relationship with Thomas Merton because when I was living at a monastery in North Winnipeg, hiding out after I’d left the music business – I’d been there for about six months – I spent a lot of time in the monastic library there. And Thomas Merton was certainly one of the people that sort of took me by the hand and led me through the great unraveling. And so then when I read Merton’s Palace of Nowhere, and then ended up attending the Living School for two years, it was a very delightful surprise to meet James there. A lot of healing came out of James’s teaching at the Living School for me. Then the first thing that we did together was an album called Sanctuary, that explored the healing path – which resonated for me in a big way because of all the healing that I received while I was at the Living School. Then after that I felt like it would be a nice tie-in to do this Pt. Vierge project because Merton had also helped me very much, plus I wanted to do another project with James.

Kolbe Times: James, for so many people – and I count myself in that group – Merton is such an important figure. Discovering him is often a total “game-changer” in many people’s spiritual journeys, as it was in mine. So I think I speak for many of our readers when I say that I would love to hear you talk a bit about your most enduring impressions of Thomas Merton from your six years spent at the Abbey of Gethsemani, where he lived as well.

James Finley: When I was growing up at home, there was a lot of trauma going on. My father was a violent alcoholic. My mother was a devout Catholic, and really through her, I turned to my faith to help me get through the things that were happening. In that context, when I was in the ninth grade and I was attending an All Boys Catholic School in Akron, Ohio, the religion instructor mentioned monasteries, and Thomas Merton, who I’d never heard of before. I remember I got his book The Sign of Jonah, the diary that he kept in the monastery, and it had a very profound effect on me. I thought that the things he was saying about God’s presence in our life were so beautiful, and in my heart I knew they were beautiful because they were true. Over the four years of high school, the violence got worse at home, and I kind of kept myself tethered to God. Also, during those four years, I felt increasingly drawn to go to the monastery.

Photograph of Thomas Merton by John Howard Griffin. Used with permission of the Griffin Estate and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University.

So I started writing to the Abbey of Gethsemani, and after a while I was interviewed and so on, and entered. At the time I arrived, Thomas Merton was Master of Novices. As a novice, I met with him for one-on-one Spiritual Direction about every other week, for an hour or so. I considered him to be the living embodiment of the lineage of the mystics down through the centuries – I saw him as a living mystic. And so I ‘sat at his feet’ in the classical sense, and was opening myself to that; how to be faithful to that. He was very compassionate towards me, and I would say he was also very real with me. It was a healing thing just to be in his presence. When I left the monastery, I continued reading him, and I started giving retreats about him. I continued to study his writings – which I’ve been doing ever since. So he’s been one of my teachers, guiding me, as part of my personal journey.

Kolbe Times: Alana, what does the name of the album, Point Vierge, refer to…and what works of Thomas Merton did you dig into for inspiration for this album?

Alana Levandoski: Point Vierge is French for ‘virgin point’, and I thought it was a nice tie-in to the title of James’s book, Merton’s Palace of Nowhere. Merton’s vision of the Point Vierge is as a mystical metaphor for the door that is everywhere and nowhere – the point of nothingness, a point of pure truth, which nobody can do anything to. James and I have a kind of similar approach in the way that we’ve both used this in our own healing journey, which ties into our spiritual journey. James also has an analogy in his teachings, in which Point Vierge is the centre of the cross, where the horizontal and vertical meet. So it’s really dancing with metaphors, and I thought it was a very similar metaphor to the palace of nowhere. The whole album hinges on getting to that – Merton himself is intuiting it as a young man, and he just continues to move forward.

The book that I used as my foundation was The Intimate Merton: His Life in His Journals. It’s a great book – a compilation of many of his journals, even prior to his conversion, and then it moves into his baptism, and World War II, and so on. And I got into Merton’s New Seeds of Contemplation, and was also very impacted by his poetry. I also used James’ book, Merton’s Palace to Nowhere, and I found Kathleen Deignan’s Book of Hours, which features Thomas Merton’s prayers and reflections, to be very helpful, too. I spent a lot of time exploring…and highlighting!

Kolbe Times: James, much of your focus has been about exploring the inner work needed to heal from trauma and how to grow closer to God in the process. I’m thinking about the trauma from the abuse that you suffered early in your life, which you have talked about quite openly, and then how your life intersected with Thomas Merton, and then you went on to help others in their healing from trauma and abuse, through your work as a psychotherapist and author and retreat leader. How do you see all those experiences fitting together?

James Finley: To me – to put it poetically – if I would look at the moments that were the most horrendous, and then if I would look at the moments in the monastery, where I was graced with these unitive experiences of God, it’s quite easy to see how, at one level, those two moments are in polar opposite of each other. And in a way they are. But what I also can see is to what extent the two touch each other, and interpenetrate each other. In that alchemy, you know, there’s kind of an enigmatic liberation.

We tend to think sequentially, like the life of Jesus, the death of Jesus, and the resurrection of Jesus. But what if they’re happening simultaneously, so that birth and death and anguish and ecstasy are unexplainably one. It’s like sometimes in having to endure the worst, you can come across what’s better than the best. And going into the darkest, darkest place, you are strangely liberated from the tyranny of darkness over your heart.

When we talk about the dark night of the soul, and these images of purification, we might like to believe that spirituality will deliver us from having to go into the painful places where we don’t want to go – and therefore spirituality can be a psychological defense against suffering. But there’s a certain way that it actually empowers us to go in to the very center of the suffering itself, and find a liberation. The Buddhists say it’s like walking through the middle of the flames and discovering that it’s raining there. So you can go to the centre of sorrow, and be liberated from the tyranny of sorrow!

I saw this so often in my own therapy, where I would risk being vulnerable in front of somebody, sharing what it felt like, inside, to be me, and I would experience this strange liberation. I’ve seen this often with trauma survivors, too, and I know what it’s like. It’s the same way with Alcoholics Anonymous. When you admit that you are powerless over alcohol, and your life has become unmanageable, instead of being annihilated with shame, you’re liberated. That’s the paradox. That’s the Point Vierge. That’s where the anguish and the ecstasy intersect each other, and it becomes kind of incandescent – this kind of oneness. So that to me is how it all fits together.

Point Vierge. Album art by Mary Haas.

Kolbe Time: It almost seems that the two albums you’ve done with Alana – first Sanctuary, and now Point Vierge – are like an extension of that work of healing and reconciliation. There’s a lovely intersection on each album between Alana’s meditative music and the words you speak to these themes.

James Finley: Yes, I think there is much that can be said about what Alana has done here. One is certainly the sense of the integrity of pursuing Merton’s life, and the way that she has very carefully tracked the autobiographical foundations of his teachings, and then carefully selected passages from his life – so that those who are familiar with his life story will recognize those passages – and then to set them to music. Beyond that, there’s almost a kind of a liturgical richness, which then echoes the liturgical richness of our life, because we realize it’s about us, really. That’s how I’ve experienced it. I think it’s that combination of singling out the essence in a few sentences and setting it to music and repeating it almost like a Taizé chant. It’s invitational, and it evokes this new awareness just by experiencing it. I think it’s wonderfully done.

Kolbe Times: People can also access a series of short videos that you’ve produced, in which together the two of you discuss each song on the album and how it refers to a part of Merton’s life. We LOVED watching them! Your discussions on the videos really open up each song and let us see inside, and they bring out so many great insights about Merton’s teachings and his life – plus it’s just a lot of fun to see the two of you banter back and forth.

Alana, can you talk a little about the depth that James brings to this project?

Alana Levandoski: Well, just as James says that meeting Merton was like meeting someone standing in the lineage of the great mystics, I get to say the same thing about James. I truly think that if I hadn’t worked with James on this album, there would have been a missing link in the chain. I think that certainly James can speak in a scholarly way about Merton, but he also looks at the ‘mystical essential’ that is offered to us if we’re willing to look. As a songwriter and an artist, I often feel that poetry is always sort of ‘at risk’ in our culture – though the cool thing is that when it’s most at risk is when it does its greatest work. So for me, as somebody who is looking at Merton from a poetic standpoint, working with James Finley is kind of a no-brainer…because he looks at him like that, too. And I just want to say that I don’t mean the word ‘poetic’ in any kind of elitist way at all. Some of my favourite poets, like Mary Oliver and David Whyte – and I love the prose of Annie Dillard – have an ordinariness in their poetry and writing. That’s another reason why I wanted to work with James. Merton had a twinkle in his eye about the ordinariness of life, and there’s a treasure to be found there. It could be one of the greatest treasures. I wouldn’t have been able to go there if I didn’t have James with me.

Kolbe Times: Poetry is making a comeback these days. You hear people talking about poets and quoting poetry more and more.

Alana Levandoski: I think whenever there’s a great turning in the history of the world, poetry will always be making a comeback!

Kolbe Times: Yes, that rings true…and it feels like this might be one of those times in history when we need all the poetry we can get. We also need resilience – and that’s the theme for this issue of Kolbe Times. Could we could end our chat together by reflecting on what that word ‘resilience’ means to each of you? I’m thinking not only about the unsettling world events swirling around us, but also the things we all have to deal with in our personal lives and in our families, like financial issues and health problems. Our youngest son has a number of neurological disorders, which has brought its own set of joys and struggles…but which I would also say has led to a certain resiliency that our whole family has developed together.

Alana Levandoski: Resilience is a tricky word, and I think our context is often about “soldiering on” and “if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” We can be almost violent when it comes to this concept of resilience. And then you’ve got this great work by Parker Palmer, who says, “Let your life speak.” He writes about how the Quakers tell us to listen when our bodies say ‘no’. For me, I think I’ve come to perceive resilience primarily as being more flexible.

I know some people who spent most of their winters down in Mexico, and they have learned how to become master cob house builders, using natural materials like soil and clay and straw. And when the ‘gringos’ come and look at their houses, they tell them ‘Oh, no, this isn’t how you construct a house! It has to be concrete’ and all the rest of it. But when storms and earthquakes come along, these sort of conventional, modern type of buildings are basically demolished, just ruined, even though they were built strictly to code. And all these cob houses, which come out of this ancient wisdom, have a flexibility built right into them. Those thousands of years of wisdom are based on the concept of the earthquake, and the hurricane, and the storms.

That’s what comes to me, as a mother of young children who have tantrums and all the rest of it. It’s about breathing with them; realizing you’re their ‘port in the storm’. It’s so very challenging in the moment, but it’s really about being there with them when they need you.

Kolbe Times: That’s so true – sometimes the most important part is just hanging in there. How about you, James? What comes to your mind when we talk about resilience?

James Finley: Here’s my initial sense, in light of what we’re talking about. I think, first of all, there’s a kind of psychological resilience that has to do with ego strength. It’s like this ability to find reserves, to cope with the things that need to be coped with. We sometimes think we can tolerate almost anything as long as the centre holds. But it gets scary when the scary thing gets into the core of us, and the centre starts to fragment – which is to be traumatized.

So there is a level at which we need to preserve the centre, so we can deal with things.

But thinking about your son reminds me of a time when I got to travel with Jean Vanier to Rome, for the International Pilgrimage for Developmentally Challenged Children. Families came from all over the world. I’ll share this image that came to me which relates to resilience, and to trauma, too. There was this priest we met in Rome who worked alongside other teachers helping developmentally challenged children and their families. He told this story. He said the teachers would sometimes sit at a table with a developmentally challenged child and play a game with them, often while the parents were watching. The teacher would put a quarter on the table and put an empty glass on top of it, and then ask the child if the quarter was still there. The child could see the quarter, so they would nod and say, “Yes!” Then the teacher would pour water into the glass, and because of the refraction of light you couldn’t see the quarter anymore. And they’d ask the child again if the quarter was still there, and this time, because they couldn’t see it, the child would say, “No.” They’d do this over and over again, and the child would keep saying the quarter was still there when it was visible, but when they couldn’t see it, the child would say, “No. It’s not there.” The child had no object constancy. They’d play this game many times, until finally, finally, the child would say, “Yes, the quarter is there” even though they couldn’t see it. And the priest said that one time he glanced over at the parents, and they had tears in their eyes. That’s mystical resilience. Love elicits something out of the depths of a situation that may be very sad…but it’s not just sad, because it lays bare resources that are beyond ourselves. It can change your life, like a pedagogy of compassion. To me, that’s resilience. A lot of the monastic life, by the way, for Merton, is about that. You’re asked to live in this poverty, and in the deepening poverty you lose your resilience. And then this underlying divine resiliency takes you to itself, in your powerlessness. Hence the gratitude. It’s amazing grace. Amazing grace.

When we have someone like one of these children in our life, in some strange way they remind us about what life is really all about. You know, like, who’s helping whom here? There’s kind of a familial resilience that we learn in these circumstances, which weaves people together.

We might also say that for Merton, this weaving together is the essence of social justice. When the world loses that, it turns to ideological harshness. So how do you rebuild the relationship between mystical union and social justice? It’s like St. Francis kissing the leper. It’s like Mother Teresa working among the dying in Calcutta. It doesn’t make any sense. But it has to do with this possibility: bringing communal resilience to the world.

Kolbe Times: Much to think about. Thank you both so much for this project of Point Vierge, and for your time with us today.

James Finley: It’s been lovely!

Check out Point Vierge: Thomas Merton’s Journey in Song to hear the album and take the album journey with Alana and James.

Learn more about James Finley at contemplativeway.org.

For more about Alana, her music and other projects, visit www.alanalevandoski.com

You can also follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Photos of Alana courtesy of Alana Levandoski.

What a lovely conversation, and with such lovely people! I feel my own journey has been joined by theirs, and theirs by mine, and it is good to have such inspirational travelling companions. Thank you for this, and for all your good work in bringing these stories to light.

You’re so welcome, Brian! And I agree – Alana and James are truly inspirational…and great fun to chat with as well!