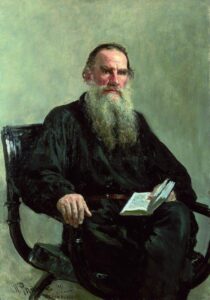

I have eagerly, addictively, read War and Peace (1869) by Count Leo Tolstoy not once, but three times. Each time I read the book, I was undergoing one of the most stressful periods in my life. It is as reassuring to me as food is to some, except the novel isn’t a single comfort meal—it’s a long comfort banquet. By the time I have finished the 1136 pages of my well-worn copy, whatever stress I am undergoing has lessened, or I have had time to adapt to my new circumstances.

Part of its gentle enchantment resides in the marvelous description of far-away places and times: the sparkle and glamour of an Imperial ball, or the mysterious fecundity of a dense Russian forest. But it is the many people of War and Peace who most captivate me. Since the time of Greek theater to the era of the soap opera, there is something cathartic about watching emotional drama played out by other people. In his great novel, Tolstoy describes, vividly and perceptively, nearly every facet of human experience: birth and death; the sufferings, fears, and even the elation of war; happy and unhappy marriages and families; poverty and wealth; physical suffering and recovery; gaiety, contemplation, and heartbreak.

Part of its gentle enchantment resides in the marvelous description of far-away places and times: the sparkle and glamour of an Imperial ball, or the mysterious fecundity of a dense Russian forest. But it is the many people of War and Peace who most captivate me. Since the time of Greek theater to the era of the soap opera, there is something cathartic about watching emotional drama played out by other people. In his great novel, Tolstoy describes, vividly and perceptively, nearly every facet of human experience: birth and death; the sufferings, fears, and even the elation of war; happy and unhappy marriages and families; poverty and wealth; physical suffering and recovery; gaiety, contemplation, and heartbreak.

Once I have remembered to differentiate between all those Russian names (“Denisov” and “Dolohov” sound so similar in their names, but aren’t in the least alike!), I appreciate the many temperaments and emotions represented in Tolstoy’s vast range of characters. As a woman, I especially appreciate that he presents some of the most sensitive portraits of women ever written: the soulful and earnest Princess Marya, the spirited but good-hearted Natasha Rostov, or the self-sacrificing but sterile Sonya. But male or female, all of Tolstoy’s characters are drawn with sensitive dimensionality, so that I identify with them and feel absorbed by their lives. Above that, the novel is infused with the beneficent vision of its author, who, in his writings and his life, advocated love, compassion, and charity. Reading the novel, I sense that Tolstoy felt that no character, and no human being, was beyond redemption. Even the more malignant characters sometimes have a hidden side; the rake Dolohov, for instance, secretly takes cares of his aging mother and sister.

True, Tolstoy sometimes launches into abstract analyses of history, but even these passages provide their own kind of comfort. They put some perspective on my own troubles, and make me feel that I, like the characters in the book, am part of something larger, and greater, than all of us.

Most comforting of all to me is the physical and spiritual renewal experienced by so many of the individuals in War and Peace. After intense grieving and recriminations when his wife dies, Prince Andrey eventually senses “an irrational, spring feeling of joy and of renewal.” Natasha Rostov, after the deaths of her beloved fiancé and brother, finally feels “delicate, tender young blades of grass” pushing through the “layer of mould under which she fancied that her soul was buried.” Pierre, after great suffering and privation, is described as becoming “so clean and smooth and fresh; as though he had just come out of a bath…a moral bath.” This renewal sometimes comes about through the characters’ selfless activity, and sometimes through a spiritual or natural force quite apart from their reason or will.

It is this promise of renewal in the novel that has resonated so strongly with me during difficult times, although I admit that the romance, drama, and occasional humor in the book have been equally compelling. Dropping into the book at the end of a long day has been like meeting up with old friends for a wonderful and enriching meal, one I can have again someday, whatever my circumstances.

Fantastic – one of my favorite novels which you have described with a sensitivity worthy of any character in Tolstoy’s book!

What an insightful tribute to a favorite novel! The best stories must age like a fine wine. Cheers!

Truly great review of a book I am now longing to read.

Thank you, Lisa, for your inspiring words.

Glad to get the encouragement too ONE DAY read this classic. I loved your 2018 Lamar University book Xuai– I wonder if you have any suggestions as to how to find a dictionary of Coahuiltecan words?