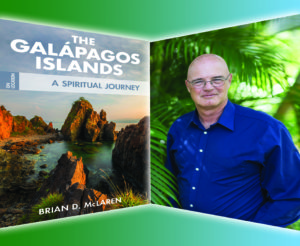

The Galápagos Islands: A Spiritual Journey by Brian McLaren

Fortress Press; 2019

Who could turn down an all-expenses paid trip to the Galápagos Islands, one of the world’s foremost destinations for wildlife-viewing – with a number of animal species found nowhere else on our planet? Brian McLaren certainly couldn’t.

The rather amazing offer came out of the blue, when McLaren was contacted by his friend Tony Jones, an editor at Fortress Press. Jones was launching a plan for a book series that would be equal-parts travel guide, spiritual memoir and ethical/theological reflection. Would McLaren like to write the first one in the series, and spend some time on the Galápagos Islands? Jones admitted he couldn’t offer an advance on the book…but would cover all expenses.

Thus, the adventure began for well-known public theologian, activist and prolific author Brian McLaren. Knowing about his life-long love for science and nature, I can only imagine how delighted he must have been at the opportunity. The experience culminated in his latest book The Galápagos Islands: A Spiritual Journey, published in October 2019.

Though I’ve been reading many of his books for years, I first got to know Brian McLaren personally while interviewing him in 2018 for Kolbe Times. In the interview, we discussed his inspiring and thought-provoking book The Great Spiritual Migration, How the World’s Largest Religion is Seeking a Better Way to be a Christian (Convergent Books, 2016). We also had a wide-ranging chat about his beliefs, passions, and life story – including his upbringing in a very strict Christian sect called the Plymouth Brethren – and his ongoing spiritual growth and discoveries as an adult.

Near the end of 2019 my husband and I had the great pleasure of seeing McLaren again, when he was in Calgary speaking on the topic of “re-wilding” Christianity. It was a fascinating evening, and the church was packed. In his talk, McLaren pointed out that most theology in recent centuries (especially white Christian theology) has been the work of “avid indoorsmen” – scholars who work in square buildings, surrounded by square books. He went on to speak passionately about the joys of rediscovering Christianity as a religion that is wild rather than domesticated, reconnecting us with soil, sun, water, and wilderness.

One of my favourite parts of his talk was when he reminded us that Jesus, in his upbringing, teaching and practical ministry, was essentially a country boy. He often disappeared into the wilderness, and seemed to love bringing nature into his stories (the “birds of the air” and the “lilies of the field”). Jesus taught on mountainsides, in boats, and on beaches; on Easter morning, Mary Magdalene mistook him for a gardener.

McLaren also talked that evening about his life-changing experiences with nature on the Galápagos Islands. A few months later, with the coronavirus pandemic upon us and travel of any kind becoming a distant dream, it occurred to me how wonderful it would be to get my hands on McLaren’s latest book and “accompany” him on his trip to the Galápagos Islands. I wasn’t disappointed.

nature on the Galápagos Islands. A few months later, with the coronavirus pandemic upon us and travel of any kind becoming a distant dream, it occurred to me how wonderful it would be to get my hands on McLaren’s latest book and “accompany” him on his trip to the Galápagos Islands. I wasn’t disappointed.

The book is a rich and delightful read. In the first half, we traipse along with McLaren and his tour group around “one of the most unique, beautiful and important ecological situations in the world,”1 His portrayals of the animals, landscapes and people that he meets on the islands are illuminating and often humorous, and his descriptions of encounters with so many amazing creatures – from iguanas to pelicans, sea lions to giant tortoises, manta rays to reef sharks – are filled with wonder and joy. I also appreciated how McLaren included his own photos from the trip, as well as some of his favourite quotes from writers, thinkers, poets and other figures.

Tortoises in particular have a special place in McLaren’s heart. As he describes in the book, he now lives in Florida “at the intersection of the Everglades and the Gulf of Mexico”2 where he is raising a small herd of tortoises and turtles in his backyard. You can sense his connection with these remarkable reptiles when he writes about the day on his trip when he and his fellow tour group members spent hours just hanging out with tortoises, overcome by natural reverence:

“Our attentive experience of self-forgetfulness and whole-hearted tortoise observation was, in a real way, ecstatic. We were taken out of ourselves in the contemplation of a creature so different from us in many ways, yet like us in others. We had fallen out of normal concerns and into love, you might say. Or risen into love. Or embarked upon it. Or leapt into it.”3

Throughout the book, McLaren intersperses reflections on his own lifelong love for nature, which was aided and encouraged by his outdoorsy father. McLaren also ruminates on some important questions that made me as a reader pause and ruminate as well – especially when he turns his pen to stories of the thoughtless destruction that has been dealt to these islands and their inhabitants in the past.

McLaren examines our present situation and future outlook, without pulling any punches: “If we don’t develop an economy and a civilization that fit our environment, we simply won’t survive.”4

As a history buff, I was also captivated by McLaren’s compelling and detailed take on the life and work of Charles Darwin. Darwin studied the animals of the Galápagos Islands for five weeks in 1835 while travelling as a naturalist on the HMS Beagle, and went on to publish his theory of evolution in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species. In the end, McLaren bemoans the fact that the figure he describes as a “good and decent man of conscience, struggling to do the right thing at the right time in the right way”5 was seen as a monster by many Christians for decades – including, as McLaren writes, “the conservative Christians in whose company I was raised.”6

The final chapters in the book are beautiful post-trip theological reflections, wide and deep, as he looks back on his Galápagos experience while encouraging us all to expand the perimeters of our ideas of ‘church’ and ‘worship’. McLaren weaves a variety of stories and themes throughout these reflections, such as trout-fishing in Yellowstone National Park, and a comparison of economic systems. Throughout, he also reflects movingly on the evolution of his own faith, and some of the important pitstops along the way.

McLaren’s “Afterword: Play” ends the book with some beautiful advice, especially relevant in these days of self-quarantine and social distancing:

“Perhaps someday you will make that flight to Baltra and begin your own Galápagos adventure. But really, the destination is far less important than the loving attention, the mindful openness, and the playful pace you bring with you next time you walk out your own front door right where you live.”7

Visit Brian McLaren’s website for his blog, upcoming events, books, and other resources.

- McLaren, Brian. (2019). The Gálapagos Islands: A Spiritual Journey. Brentwood, TN: Fortress Press. Xvii.

- Ibid, 4.

- Ibid, 206.

- Ibid, 262.

- Ibid, 163.

- Ibid, 149.

- Ibid, 277.

Inside an Ancient Rhythm

I was very young with this energy signature of fear,

a grip of tension embedded deep in my gut,

brought in from Another Time.

It sounds like these clicking computer keys:

tap tap tap,

the clatter of a mind with the 3 a.m.

blah blah blahs of small worries.

Like unanswered emails,

their blue warning dots demand response,

jarring me into a wide awake nervous fret.

Or: Drip drip drip

the inner water torture of endless to do lists

inciting a harried rush from this-to-that,

fueling an addiction to activity that keeps me

on the surface of things.

Or the rapid, reactive:

thump thump thump

of a heartbeat when feeling

insulted, afraid or threatened.

Tap, drip, thump escalate to:

boom boom boom

with Big Worries,

a tribal nervous system of pulsing fears:

disappearing bees, polar bears, ozone.

Wars, so many wars.

The seductive, deafening noise of these times.

Sometimes beneath this cacophony

a Gong is heard.

Here, deep, prolonged fog-horned crescendos

summon my soul,

intoning, “You are so much more than this.

Return to me. Rest in Me.”

You could be ready

to live inside an Ancient Rhythm.

Let me ring you home.

From The Everywhere Oracle: A Guided Journey Through Poetry for an Ensouled World

Used here with the author’s permission.

Poem for a Winter Solstice

One morning you raise the east window blinds

and there is the sun, hunched on the horizon,

doing its best to break free, shunting aside

a few clouds as it hoists itself in readiness to skate

a frigid rink of sky, firing that cloud layer

with an intense roseate glow, deceptive warmth.

This is winter morning, you say to yourself,

but then you realize – and it comes as a shock –

that the sun has risen so far south, you feel

your house has been wrenched a quarter-twist

to the right while you slept. You check your watch –

Migod, it’s coming nine o’clock.

When did this happen?

The wall calendar tells you it’s December,

but something deep within you has clung

to the lingering warmth of snowless autumn.

The body deplores this retreat towards the dark,

the dimming days, the physical affront of cold.

Already, unseen crevices within us are busy

re-programming the spirit for spring.

This Moment, Yearning and Thoughtful

This moment yearning and thoughtful, sitting alone,

It seems to me there are other men in other lands, yearning and thoughtful;

It seems to me I can look over and behold them, in Germany, Italy, France, Spain

or far, far away, in China, or in Russia or India,

talking other dialects;

And it seems to me if I could know those men, I should become attached to them,

as I do to men in my own lands;

O I know we should be brethren and lovers;

I know I should be happy with them.

2019 is the 200th anniversary of Walt Whitman’s birth. This poem is in the public domain.

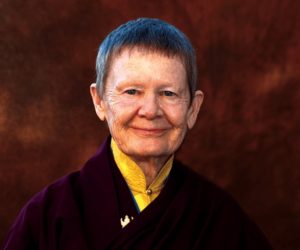

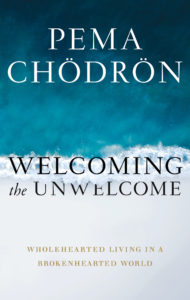

Welcoming the Unwelcome: Wholehearted Living in a Brokenhearted World by Pema Chödrön

Shambhala Publishing

October 2019

Pema Chödrön is an American Tibetan Buddhist and best-selling author of over 20 books. I first came across the beloved Buddhist nun and spiritual teacher when a friend gave me The Pocket Pema Chödrön for Christmas a few years ago. This little paperback, filled with short selections from her many decades of study and writings, has stayed in my purse ever since – and is definitely looking more than a little tattered. Whenever I find myself waiting in line somewhere, with time on my hands, I bring it out. Even though I’ve read it through a few times already, it never fails to encourage and inspire me. I now firmly count myself among this 83-year-old Buddhist nun’s legion of fans throughout the world.

Ani Pema (“Ani” is a prefix added to the name of a nun in Tibetan Buddhism, akin to “Sister” among Catholic nuns) was born Deirdre Blomfield-Brown in New York City in 1936. After what she describes as a pleasant Catholic childhood, she married at the age of 21, went on to study at the University of California at Berkeley, and became an elementary school teacher. She had two children with her first husband, but divorced in her mid-twenties and remarried years later. Her second marriage came to an end when her husband revealed he was having an affair and wanted a divorce.

Ani Pema came to explore her spirituality as an attempt to cope with the emotional trauma of her failed marriages. She cites the moment her second husband revealed his affair to her as a genuine spiritual experience – a moment where time truly stood still. To cope with her pain, Ani Pema sought various forms of therapy. It took a year filled with fear, rage and what she describes as general “groundlessness” for her to begin piecing her life back together.

Her true awakening began when she came across an article about Buddhist concepts written by the man who would become her most influential teacher, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. The article suggested making peace with discomfort rather than trying to banish it. Sparked by an interest in his teachings, Ani Pema went on to study with Lama Chime Rinpoche on frequent trips to London, and became a novice Buddhist nun in 1974. Lama Chime encouraged her to work with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and she studied under him from 1974 until his death in 1987. She received the full bhikshuni ordination in the Chinese lineage of Buddhism in 1981 in Hong Kong.

Ani Pema served as the director of the Boulder Shambhala Center, a retreat center in Boulder Colorado, from 1981 to 1984, and then went on to help establish Gampo Abbey in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. The Abbey, completed in 1985, was the first Tibetan Buddhist monastery in North America for Western men and women, and Ani Pema took on its directorship. She remains to this day as the spiritual director of Gampo Abbey, which she credits as being the place where she truly let go of fear and ego. She continues to help establish the monastic tradition in the West, teaching in Canada and the United States – though she looks forward to an increased amount of time in solitary retreat in the future, under the guidance of her current teacher Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche.

Ani Pema’s first book, The Wisdom of No Escape, was published in 1991, followed by Start Where You Are in 1994, and When Things Fall Apart in 1997. Readers were moved by her earthy, insightful teachings, and her retreats became full to overflowing wherever she went. Over the years her fame as a teacher has grown, and she is the best-selling author of over twenty books. Oprah Winfrey calls her “one of the most influential voices in contemporary spirituality, the writer whose books are passed from friend to friend.”

Welcoming the Unwelcome: Wholehearted Living in a Brokenhearted World (Shambhala Publications; October 2019) is Ani Pema’s first new book in over seven years. I was delighted to hear that she is still writing and sharing her wisdom – and thought that the title of her latest book sounded very relevant for our times.

In her new book, Ani Pema addresses important, germane areas of life that are a struggle for many of us, in chapters such as Overcoming Polarization, The Fine Art of Failure, How Not To Lose Heart, and Experiencing Nowness.

She opens the book by asking us why we engage with spiritual teaching. What is our intention? To learn how to better deal with all the uncertainty in our lives? To gain wisdom about ourselves? To help escape certain emotional or mental patterns that undermine our wellbeing?

Those all are good reasons, but Ani Pema points out that her Mahayana Buddhist tradition arouses another motivation, called “bodhichitta”. In the Sanskrit language, “bodhi” means “awake”, and “chitta” means “heart” or “mind”. So, in her tradition, the aim of engaging with spiritual teaching is to fully awaken our hearts and minds, not only for our own personal wellbeing, but also to bring benefit, solace and wisdom to others. As she puts it, an awakened heart brings with it “the wish to be free from whatever gets in the way of our helping others.”

So how do we achieve an awakened heart – one that will truly benefit others? The advice she gives might seem surprising. It’s advice that she herself received from her teacher Trungpa Rinpoche: begin with a broken heart.

In other words, instead of avoiding our feelings of sadness or discomfort or pain, we need to allow ourselves to experience them. When we give ourselves the freedom to connect and just “sit” with our own raw feelings of loneliness, embarrassment, jealousy, anger, or shame, we increase our capacity to be present to the suffering of others. We find ourselves “standing in the shoes of humanity” – with a growing sense of courage, and a longing to help those around us.

So much of the wisdom in this book harmonizes with my Christian faith, such as cultivating compassion for others, developing a practice of meditation, increasing our appreciation for the beauty around us, and living in the present moment rather than worrying about the past or the future. All these practices and principles have also been modelled by many of the Christian figures throughout the centuries who have guided and enlightened my faith.

I also appreciate how Ani Pema writes very openly in this book, using stories about her own flaws and heartbreaks to lead us into new truths about ourselves. She models a great sense of humour about her shortcomings, and isn’t afraid to share the sometimes difficult path she has traveled to learn important lessons – all of which makes for fascinating reading. She writes movingly about learning to see the basic goodness in the people she lives with, the strangers she meets…and in herself.

She also provides a number of examples of easy but very effective practices that have made a difference in her life, and which I want to incorporate in my own mental health toolbox. Here are just two examples:

- Get in the habit of looking at people around you, whether they are strangers, friends or family members, and say these words to yourself: “Just like me.” In other words, recognize that, just like you, this person: loses it sometimes; doesn’t like feeling uncomfortable; wants to be admired; gets embarrassed easily; often feels insecure.

- This one I have especially enjoyed – a practice that helps us “be in the moment” by taking mental snapshots. Close your eyes, turn your head in any direction, and then abruptly open your eyes and take a few minutes to “see” what’s in front of you. I’ve been delighted how this simple practice has helped me slow down and perceive ordinary things in fresh and stimulating ways.

I also appreciated the three step-by-step guides at the end of the book that can help bring light to the darkness we all face at times. The first is a guide to a basic sitting meditation, which Ani Pema describes as a “golden key that helps us to know ourselves”. The second takes us through a Tonglen practice, which is a method for connecting with suffering – our own and that which is all around us – to help us overcome our fears. The third is called LESR, which stands for “locate, embrace, stop, remain”. This practice is an easy-to-remember way of combining some of the practices in the book that can help us open our hearts and minds in the places where we all habitually contract and go inward. All these practices can assist us to “welcome the unwelcome”, and learn to live life with greater awareness and compassion.

For more information, visit www.gampoabbey.org and www.pemachodronfoundation.org.

Let This Darkness Be a Bell Tower

(From Sonnets to Orpheus II; translation by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows)

Quiet friend who has come so far,

feel how your breathing makes more space around you.

Let this darkness be a bell tower

and you the bell. As you ring,

what batters you becomes your strength.

Move back and forth into the change.

What is it like, such intensity of pain?

If the drink is bitter, turn yourself into wine.

In this uncontainable night,

be the mystery at the crossroads of your senses,

the meaning discovered there.

And if the world has ceased to hear you,

say to the silent earth: I flow.

To the rushing water, speak: I am.

Big Things: Ordinary Thoughts in Extraordinary Times by Gerry Turcotte

Review by Laura Locke

Gerry Turcotte has done it again.

His 2016 book, Small Things: Reflections on Faith and Hope (reviewed in our Spring issue of that year) was a compact collection of short essays that splendidly confirmed the old adage that “good things come in small packages”.

I was excited to hear that Turcotte, who is the President of St. Mary’s University in Calgary and an award-winning author, has gifted us this spring with a new compilation of essays – this time entitled Big Things: Ordinary Thoughts in Extraordinary Times.

Turcotte’s latest collection again showcases his perceptive insights and personal warmth. He doesn’t shy away from poking fun at his own mistakes and foibles, drawing upon his everyday experiences as a father, son, teacher, community leader, writer, and the head of a fast-growing university. Weaved throughout the 52 essays, one for each week of the year, is also a searching and honest exploration of his Christian faith, along with many glimpses of his heartfelt dedication to social justice issues, such as the rights of Indigenous peoples. As he points out, “all social justice initiatives begin with a small voice that is amplified by conviction and belief” – and so it is with these captivating essays that Turcotte has penned, which might be likened to seeds that, once planted in our imaginations, can take root and grow.

I appreciate very much how each essay begins with a verse from the Bible, setting an interesting context for the discussion to follow. However, Turcotte tells us that he is “at pains to point out that I am not a theologian but a writer and commentator, and one who has brought his own eclectic way of looking at the world to the idea of faith in our times.”

setting an interesting context for the discussion to follow. However, Turcotte tells us that he is “at pains to point out that I am not a theologian but a writer and commentator, and one who has brought his own eclectic way of looking at the world to the idea of faith in our times.”

Eclectic, indeed! The essays are about an engaging assortment of broad-ranging, multifaceted topics, filled with memories, stories and thoughtful ruminations. Here are a few examples:

- A delightful essay entitled A Higher Craft, about growing up in a rather ramshackle hardware store owned and operated by his Dad. Turcotte recalls the store as a magical place with crawl spaces, trap doors and false walls that were “the envy of any medieval castle”. His Dad knew the name and purpose of each and every tool in the store, which seemed to his young son as nothing less than the naming of the magic of the universe, as it lived in everyday objects.

- A fascinating discussion on the ancient notion of “scapegoats” – how the term was initially an incorrect translation of another word, and how it came to be used throughout the centuries. Turcotte then turns to the “driving thread” of Pope Francis’ encouragement to resist the search for scapegoats, and instead to “take responsibility for our actions, our words, our thoughts; whether this has to do with climate change, acceptance of refugees or responsibility to the poor.”

- A perceptive exploration of the “intoxicating and immediate bedazzlement” of today’s technology in an essay called Note to Selfie. I enjoyed how Turcotte compares selfies to the “long and respectable history” of self-portraits in art. He then leads us into a reflection on how a resonant faith can give us a way to look “deep within”, instead of only at the surface.

In his essays, Turcotte has a lovely way of meandering through his own history of epiphanies, lessons learned, and wake-up calls, accompanied by a healthy dose of humility and lots of room for laughter. He also brings into the light a number of issues that he finds troubling, puzzling, or simply intriguing – and invites us to join him on his journey of wonder and self-discovery. Which, speaking on a personal note, is indeed a great privilege and pleasure.

Eternity

I could see the constellations

in the sparkle of your eyes.

I assumed that you were ready

to behold the brave o’erhanging firmament

the majestical roof

fretted with golden fire.

I thought that I could teach you

the music of the spheres.

Would you like to see

the universe tonight—the one

that spreads its blanket

of a billion starlights over us?

Quickly the lights flickered from your eyes.

Sadness spread across your face.

You clutched your little arms

to heart. Not yet. Not yet. Suddenly, as grandmother,

I understood. Three year olds

have only just escaped the Void

into this Consciousness.

They are not ready

to look back just yet.

We older wiser souls are no longer afraid.

We eagerly let our thoughts fall up

into the welcoming arms

of forever.

At our age we can finally

bear the wonder.

Used by permission of the author.

I Am the People, the Mob

I am the people—the mob—the crowd—the mass.

Do you know that all the great work of the world is done through me?

I am the workingman, the inventor, the maker of the world’s food and clothes.

I am the audience that witnesses history. The Napoleons come from me and the Lincolns. They die. And then I send forth more Napoleons and Lincolns.

I am the seed ground. I am a prairie that will stand for much plowing. Terrible storms pass over me. I forget. The best of me is sucked out and wasted. I forget. Everything but Death comes to me and makes me work and give up what I have. And I forget.

Sometimes I growl, shake myself and spatter a few red drops for history to remember. Then—I forget.

When I, the People, learn to remember, when I, the People, use the lessons of yesterday and no longer forget who robbed me last year, who played me for a fool—then there will be no speaker in all the world say the name: “The People,” with any fleck of a sneer in his voice or any far-off smile of derision.

The mob—the crowd—the mass—will arrive then.

This poem is in the public domain.

Harrowing

The plow has savaged this sweet field

Misshapen clods of earth kicked up

Rocks and twisted roots exposed to view

Last year’s growth demolished by the blade.

I have plowed my life this way

Turned over a whole history

Looking for the roots of what went wrong

Until my face is ravaged, furrowed, scarred.

Enough. The job is done.

Whatever’s been uprooted, let it be

Seedbed for the growing that’s to come.

I plowed to unearth last year’s reasons—

The farmer plows to plant a greening season.